You know who Southern man don’t need around, anyhow? If you guessed Neil Young, you’re wrong. The correct answer is Dixie Dregs, who thought it would be a swell idea to take Southern rock as the starting point for their fearless (and fear-inducing) forays into jazz fusion and progressive rock. I solely attribute their “contributions to music” as the reason the Confederate States of America lost the Civil War. Which I guess makes them heroes of a sort.

I’m no Southern man but I’m a Southern rock fan, and I’m here to tell you there are things that should not be. And Southern rock jazz fusion/progressive rock is one of them. Dixie Dregs—they came up with the name themselves, taking it right out of my mouth—were (ahem are, they’re still out there somewhere) like a deranged bartender. They threw Southern rock and jazz fusion and progressive rock in a shaker and the resulting drink would have made Ronnie Van Zant see red.

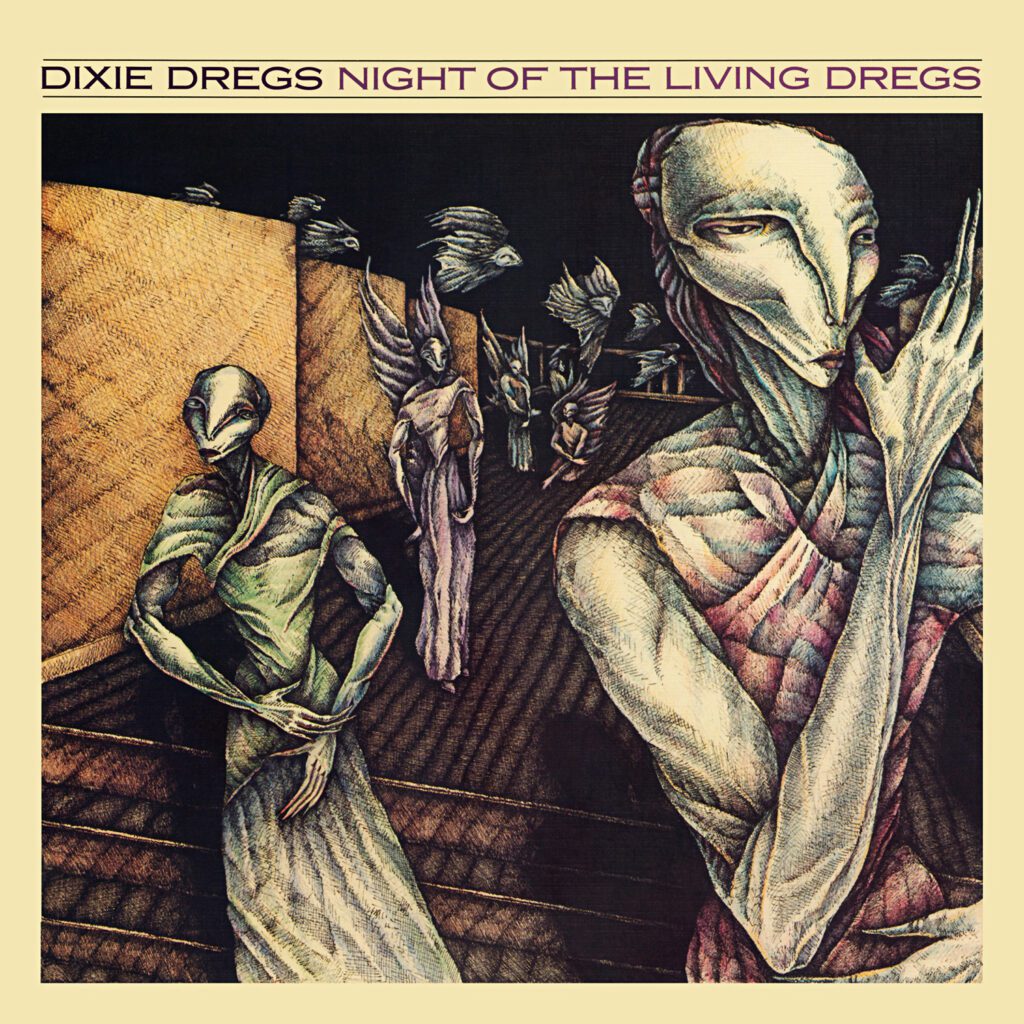

1979’s Night of the Living Dregs (the band’s third LP) is a hybrid too—the first side was recorded in the studio, the second at the Montreux Jazz Festival. Evidently the Swiss will listen to anybody and anything. And if the album’s any indication, they will like and applaud it. Not fighting a military battle in 500 years has obviously turned them into total degenerates.

Interesting line-up, though. Guitarist/songwriter Steve Morse would go on to do a brief stint in a past-their-prime Kansas before going on to do a very, very long stint with a post-Richie Blackmore, past-their prime Deep Purple. Bassist Andy West went on to play with the likes of Henry Kaiser and Little Feat’s Paul Barrere. He must be good, right? I’m not so sure. Mark Parrish, who plays keyboards, is not as ostentatious as their original keyboardist Stephen Davidowski, which is a relief.

Allen Sloan—who plays strings, violin mostly—is very flashy, and you can tell he wants to be Jean Luc Ponty when he grows up. “Percussionist” Rod Morgenstein has also played with Winger, which is definitely cooler than playing with Kansas or Deep Purple or Henry Kaiser or Paul Barrere. In fact it’s the coolest thing ever. You may have noticed that none of these guys went on to play with Molly Hatchet or Dicky Betts. Southern rock just isn’t their style.

It should be said from the outset that the Dixie Dregs’ fusion of Southern rock and jazz fusion is largely a fiction. The Southern rock touches are there, and on their first album they were clearly defined in songs such as “Refried Funky Chicken” and “Moe Down,” but by 1979 and Night of the Living Dregs a casual listener could be excused for missing them altogether. There’s some barn dance in a couple of these songs, but the barn is a theoretical and formal barn and the cows inside the barn are theoretical and formal cows. You cannot clog dance to these songs. You are hereby invited to throw your clogs at them.

Southern rock’s other fusion band, Sea Level, may have been a study in mediocrity, but they never forgot they used to be members of the Allman Brothers Band, and their music, while lackluster, is made in the same, friendly, aw shucks spirit of “Jessica.” Most of it is easy-listening dreck, but they tried to inject their music with a bit of the old Georgia Peach. It has a human touch. Dixie Dregs are jazz fusion artists to the core, and their music has all the warmth of nuclear winter. They nail that inhuman jazz fusion feel. Their songs are “exercises,” chances to show off their chops. They came out of the South and cashed in on the South but I would wager they couldn’t pick “Sweet Home Alabama” out of a police line-up. Any one of the songs from Jeff Beck’s Wired, different story.

Why, by 1979 they’d drifted so far from their swamp gator roots they open Night of the Living Dregs with “Punk Sandwich,” which CBGB man don’t need around, anyhow. It was their attempt to prove they could beat the punks at their own game, I suppose, but they didn’t have a clue. There’s no denying that Morse plays a tough rock riff and the song has both punk velocity and an actual bottom (for a change), and if I HAD to play one of the songs from the album it would be this one. But there’s also no denying that when the boys get around to taking turns on solos what you’re hearing is standard jazz fusion—slick, competent, show-offy, antiseptic and did I say slick? Slick to within an inch of its life. Miles Davis’ jazz fusion was punk rock of a sort. It was dangerous. This music is as safe as electric milk.

There’s no country in the uptempo “Country House Shuffle”—and aren’t shuffles supposed to be slow? On the plus side, Morse again demonstrates that he knows how to play a big rock riff, and his solo is meaty as well. But everything else has that weird processed electric sound that fusion bands work so hard to get for reasons I’ll never understand. Morgenstein keeps things interesting on drums. Sloan’s a ham on violin. Parrish is a ham on keyboards. Maybe they should have called this baby “Country Ham.”

“The Riff Raff” is Renaissance Faire music. Very pretty and delicate and semi-classical in a vague way and awful in a clearly apparent way. Follow-up and studio side closer “Long Slow Distance” is a long slow bore, easy-on-the-ears mush. It opens with some Liberace piano, then meanders towards inanity. No, that’s not right. It rushes towards inanity and breathes a sigh of relief when it gets there. The keyboards are blindingly bright, the violin is blindingly boring, and Morse’s turn on guitar is so tasteful and sensitive you’ll want to press charges, but believe it or not, taste and sensitivity aren’t crimes!

Side Two opens with crowd applause, which I find sinister. It’s followed by the faceless and bland “Night of the Living Dregs,” which has a beat but not a pulse. The beat isn’t just welcome—it’s all the song has going for it, and I can literally only listen to it by focusing my complete attention on Morgenstein’s drumming and pretending everything else is just a waking nightmare.

“The Bash” is a hoedown from Hell, with Sloan as Charlie Daniels (he wishes) and Morse as Chet Atkins (as if), but if this is Southern rock I hate Southern rock because it’s all so finicky and mannered and what you get instead of passion is virtuosity, and these guys are not virtuosos. They’re slick professionals working a con on the Montreux crowd, who god help them may actually have walked away from the show thinking they’d heard some by gum country music when anyone who grew up within a thousand miles of a barn could have told them this barn don’t hunt.

“Leprechaun Promenade” employs a Steely Dan riff I can’t put a name on, and otherwise makes hay out of dynamics and lots of tempo changes and swift shifts of gear which not only make it a progressive rock song, they make it hands down the most annoying song on the album, perhaps the most annoying song released in the year 1979 even, because its pretentiousness reaches Yes levels. Fortunate for all it doesn’t have Yes song length.

Like “The Bash,” “Patchwork” has a bit of the South of the Mason-Dixon Line in its DNA, but it has a real scholarly sound that gives you the impression these guys learned what they needed to know about music at college instead of playing in shitty bar bands, which is exactly the case for all of ‘em but Morgenstein. What I hear can best be described as “dueling scholars,” although Morse gets some good licks in and his guitar doesn’t have that horrible Jeff Beck processed sound, like you squeezed all the notes really hard so you could put a whole bunch of ‘em in a can. I hereby suggest the song’s name be changed to “Down South Pukin’.”

When it comes to jazz fusion, I’ve always been of the opinion that Miles Davis owes the world an apology. He got it brilliantly right, and inspired legions to do it terribly wrong. So I am not an objective critic of the genre. That said, I grew up in the country and am quite familiar with the smell of pig shit and that’s what I smell when I pull this baby out of its sleeve. Dixie Dregs are an average jazz fusion band at best who set out to differentiate themselves from the pack through gimmickry, namely by spicing up their workmanlike jazz fusion workouts with faux Southern flavoring that had nothing to do with Jacksonville or Muscle Shoals or Yoknapatawpha County or any other Southern place, real or fictional. I have reason to believe they bought said flavoring in a stir-in packet.

The most damning thing to be said about Dixie Dregs is that when all is said and done, I’ll bet your average barn dancer would be better able to relate—and dance to—Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s take on Aaron Copeland’s “Hoedown” than to anything these suspect Dixie boys ever put on record. At least ELP stay on point. And if the Dregs can’t do better than a trio of pompous Limeys I hereby submit that they be run out of the Southland “Gimme Three Steps” style. Although if it were up to me, I’d only give them two.

GRADED ON A CURVE:

D-