Remembering Gram Parsons, born on this date in 1946. —Ed.

You’ve got to hand it to Gram Parsons; the boy had chutzpah. No sooner had the relatively unknown 21-year-old joined The Byrds in February 1968 in the wake of the departure of David “I Am the Walrus” Crosby and Michael Clarke, he managed to talk the band, including leader Roger McGuinn, into scuttling McGuinn’s plans for an ambitious double album of the history of American popular music in favor of an album of straight-up country music, or country-rock if you insist, or “Cosmic American Music” as Parsons poetically termed it.

To add authenticity, The Byrds (McGuinn on acoustic guitar, banjo, and vocals; Chris Hillman on bass, mandolin, acoustic guitar, and vocals; Parsons on acoustic guitar, piano and organ, and vocals; and Kevin Kelley on drums) wrangled up a crew of mostly Nashville ringers, including legendary electric guitarist Clarence White (who would die tragically in 1973, hit by a drunken driver); John “Tear Down the Grand Ole Opry” Hartford on banjo, fiddle, and acoustic guitar; Lloyd Green and JayDee Maness on pedal steel guitar; Roy Husky on double bass; and Earl Poole Ball and Barry “Electric Flag” Goldberg on piano.

Parsons’ tenure as a Byrd turned out to be short-lived—he soon went on to form The Flying Burrito Brothers with Chris Hillman—and the Sweetheart sessions ended in controversy and chaos, with McGuinn (the original Lou Reed!) erasing Parsons’ vocals on three songs during post-production and rerecording them himself, leaving Parsons as lead vocalist on just three cuts. The ostensible reason for this varies from unresolved contractual questions about Parsons to McGuinn’s refusal to be upstaged by the unknown rich boy in his spiffy psychedelic-drug-and-pill-themed Nudie suit (which, in the interests of historical authenticity, he probably didn’t purchase until later.)

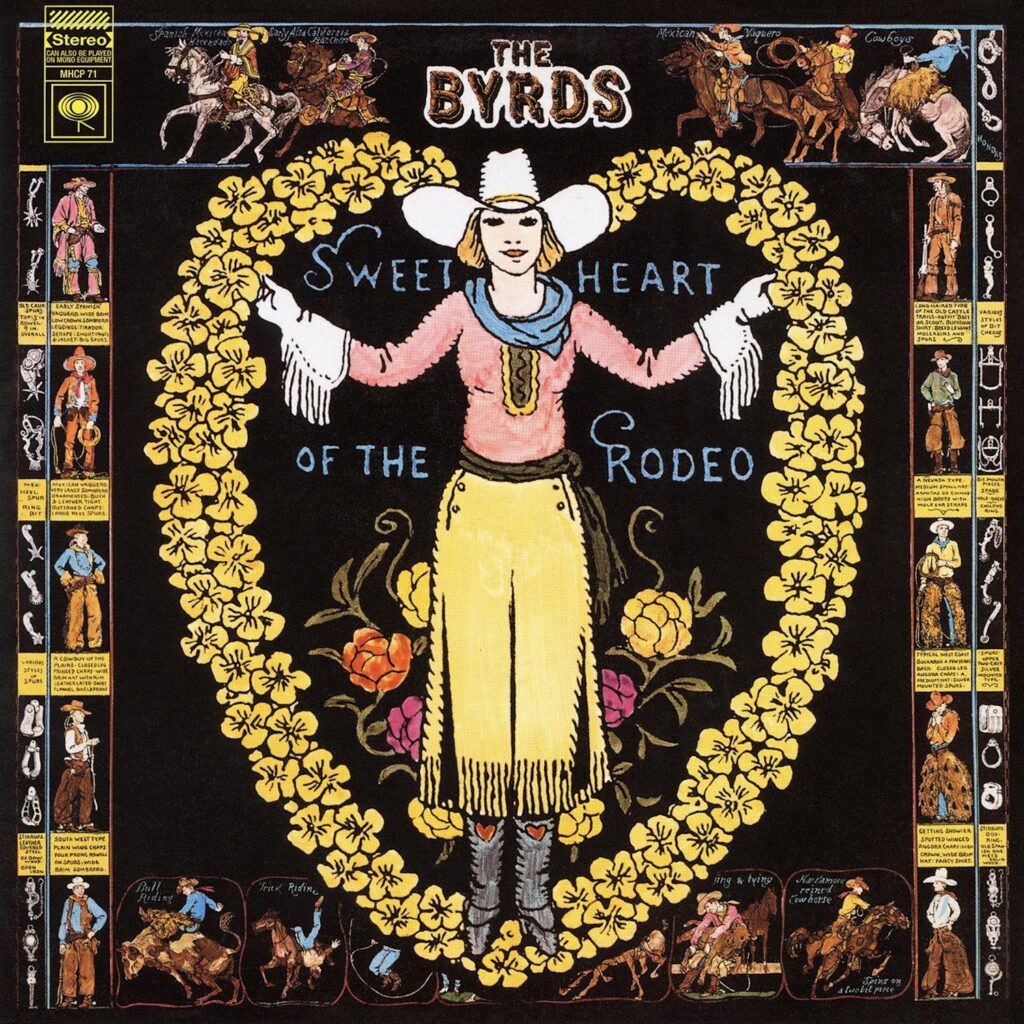

The resulting album, 1968’s Sweetheart of the Rodeo, is—with the exception of two Parsons’ originals—an album of covers of songs by the likes of Bob Dylan (the old Byrds fallback), Woody Guthrie, Merle Haggard, William Bell, and Charles and Ira Louvin (Ira, a notorious drunk and womanizer, so filled his third wife’s heart with love she shot him four times in the chest and twice in the hand; a hardscrabble Baptist, Ira lived on.) Sweetheart of the Rodeo more or less tanked, what with all the dayglo freaks who loved The Byrd’s previous acid-friendly LPs scratching their heads and saying, “I can’t smoke dope to this hillbilly shit, maaan.”

Ah, but how well it has stood the test of time. Opener “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” a Dylan Basement Tape cover, is smooth as buttermilk and sweet as Tupelo honey, and boasts a jaunty beat, McGuinn’s mellow vocals, lots of wonderful pedal steel guitar by Lloyd Green, and great backing vocals on the chorus. I’ll never like it as much as I do Dylan and The Band’s version, which is less polished and more joyous to my ears, but The Byrds’ version is nothing to sneeze at.

The midtempo “I Am a Pilgrim” is a lovely, low-key, homespun number, featuring fiddle by John Hartford, banjo by McGuinn, and double bass by Roy Husky. Lead vocalist Hillman does a wonderful job of singing about The Life Beyond; he sounds nostalgic for a place he’s never been, and where his people are awaiting his arrival. In short, it’s a pretty yet doleful number, as is appropriate for a song about a fellow who considers life on Earth a trial to be borne to reach his real home in a city “not made by hand.”

The Byrds play the Louvin Brothers’ “The Christian Life” straight, with McGuinn managing to sound authentically country as he sings—to the accompaniment of some piercing pedal steel guitar by JayDee Maness and electric guitar by White—“My buddies tell me that I should have waited/They say I’m missing a whole world of fun.” The song opens with some great pedal steel and electric guitar, and is far bouncier than you’d expect for a song about walking in the light of the Lord, and boasts a defiant chorus (“I like the Christian life!”) you’ll want to sing at the top of your lungs whether you be Christian, Jew, Jack Mormon, Muslim, or Aleister Crowley.

“You Don’t Miss Your Water,” another surprisingly perky yet sad number, is dominated by Ball’s superb piano, while Maness contributes a fine little solo on the pedal steel guitar. While McGuinn is credited as lead singer I hear more than one voice in there, which could be the traces—supposedly still audible—of Parsons’ original lead on the song. “You Don’t Miss Your Water” is every bit as smooth as “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” boasts a Dylanesque chorus (“You don’t miss your water/Till your well runs dry”), and is one of my favorite cuts off the LP.

As is follow-up “You’re Still on My Mind,” a Luke McDaniel-penned honky-tonker featuring Parsons on lead vocals, a great chorus (“An empty bottle/A broken heart/And you’re still on my mind”), and more great keyboard tinkling (sharp as a bob wire fence) by Ball and pedal steel guitar by Maness. Parsons had the most authentic country voice of anybody in The Byrds and it works wonderfully in this lovelorn bender of a song, which opens with the great lines, “The jukebox is playing a honky tonk song/One more I keep sayin’/Then I’ll go home.” Oh, I’ve been there, people, I’ve been there, and in real country bars with the TV perched precariously atop a stack of Rolling Rock cases and David Allen Coe’s “If That Ain’t Country” on the jukebox illuminating a dark corner of the bar and stickers in the urinals saying “The KKK is watching you.”

Woody Guthrie’s Depression-era ode to “Pretty Boy Floyd”—who may have been a criminal, but “you’ll never see an outlaw take a family from its home”—is up next, and it kicks along like a fleeing mule, scairt by the sound of Hartford’s jaunty fiddle and banjo and Hillman’s sprightly mandolin. The banjo opening is swell, McGuinn does a fine job on vocals, and Hartford’s banjo solo and Hillman’s following mandolin solo lead perfectly to the song’s most famous lines, “As through this life you travel/You’ll meet some funny men/Some rob you with a six-gun/And some with a fountain pen.”

The classic Parsons’ number “Hickory Wind” is next, and while I infinitely prefer the later Parsons-Emmylou Harris duet of the song The Byrds’ version is still quite fine, what with Hartford’s fiddle, Green’s pedal steel guitar, McGuinn’s acoustic guitar, and Parsons’ piano contributing to a full, rich sound that is as sad and lonesome as a frigid fall wind blowing through the dying leaves of a lone hickory tree. It doesn’t get any more country than this, and it’s a testimony to Parsons’ genius that he could hang with the Rolling Stones and still write songs every bit as good as the ones by the country greats he so loved.

Parsons’ “One Hundred Years From Now” gets the classy Byrds’ vocal treatment, with McGuinn and Hillman singing in lovely harmony. Unlike “Hickory Wind,” this one is as much rock as country, with the upbeat melody and Kelley’s drumming screaming rock while Green’s fancy dan pedal steel guitar playing chimes country. White also tosses in some nice electric guitar licks, while McGuinn and Hillman sing, “Nobody knows what kind of trouble they’re in/Nobody seems to think it all might happen again,” which I have no idea what it means but it makes me think about Nietzsche’s concept of Eternal Recurrence and how if I have to live my blighted life over and over unto infinity I am horribly fucked.

I find Cindy Walker’s “Blue Canadian Rockies” a mite boring, because I hate nature and hate songs about the beauty of nature and nature, in my humble opinion, can go fuck itself. Plus the melody ain’t much to write home about, although Hillman does a nice job on the vocals and White and Parsons play some tasty guitar and piano, respectively. And I don’t have much more to say about “Blue Canadian Rockies,” except that it makes me blue that The Byrds saw fit to include this proto-John Denver paean to the mountains (where you’ll more than likely be kilt daid by a moose or gubmint-hatin’ survivalist) on this most excellent LP.

Parsons sounds like pure country on Merle Haggard’s perky—for a song about a fellow looking at a life sentence—“Life in Prison.” Maness delivers a sprightly performance on the pedal steel, while Ball plays a nice piano, and the rhythm section is tight and keeps things moving like a train chug-a-lugging—like a bittersweet reminder of freedom—past the prison yard. There’s a great breakdown in the middle, with Maness and Ball mixing it up while Kelley makes good use of the cymbals, and while I’ll never like “Life in Prison” as much as Haggard’s other great prison song, “Mama Tried,” it’s a hot tamale nonetheless.

The Byrds close down the rodeo and kiss their sweetheart goodnight with a take on Dylan’s great and haunting “Nothing Was Delivered,” another song written in the basement of the house called Big Pink with The Band in 1967. It opens with some tasty pedal steel guitar by Green, and moves at a faster pace than Dylan’s version, and loses, I’m sorry to report, something thereby. That said the chorus is great, what with the boys singing in harmony, and Green and Parsons on piano play a nice little instrumental breakdown, which Green and Kelley then follow with a breakdown of their own. Far more polished than the Big Pink original, The Byrds’ version lacks the sense of cryptic mystery that Dylan’s vocals lend to the song, which is about an unspecified debt owed and reeks with menace only to end with the absurdly innocuous lines, “Nothing is better/Nothing is best/Take care of your health/And get plenty of rest.”

Sweetheart of the Rodeo was a brief, jukebox-bright flash of pure country light in The Byrd’s discography. By the following year’s horribly named Dr. Byrds and Mr. Hyde, McGuinn and company would be giving their obligatory Dylan cover (“This Wheel’s on Fire”) the rock treatment and laying down power chords on “Bad Night at the Whiskey,” although they threw in a few great country tunes like “Drug Store Truck Drivin’ Man.” Overall, though, they took a turn, turn, turn away from Parsons’ “Cosmic American Music” in favor of hippie-pleasing ditties like “Child of the Universe.”

Still, Sweetheart of the Rodeo was the first album to ask the children of Aquarius “Are you ready for the country?” And it remains one of the finest. The freaks may have said no, but they’d soon change their minds, and Dylan, The Band, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band (whose Will the Circle Be Unbroken is definitive), and countless others would benefit, dressing like Bammer bootleggers and saying “Howdy” like good ole boys instead of “Far out!” And the rodeo goes on still, and for that we owe both The Byrds, and the late Gram Parsons, whose funeral pyre in the Joshua Tree National Park is said to be still visible on certain haunted nights, a heartfelt muchablige.

GRADED ON A CURVE:

A