In The Radio Phonics Laboratory, the latest book from Velocity Press, Justin Patrick Moore looks at the intersections between technology and music throughout the 20th century to trace the evolutions in telecommunications that shaped electronic music. In this excerpt, he looks at the origins of the Telharmonium–the first electronic musical instrument.

In the early phases of our telecommunications technology Thaddeus Cahill obsessed over and created what must be considered the ultimate behemoth of a musical synthesizer, the Telharmonium, a type of electrical organ. Cahill, like Elisha Gray who had invented the musical telegraph, had also been a student at Oberlin College, where he studied the physics of music. Cahill took inspiration from Gray’s earlier invention, but thought it could be much improved, and intended to create an instrument to be played over the phone lines.

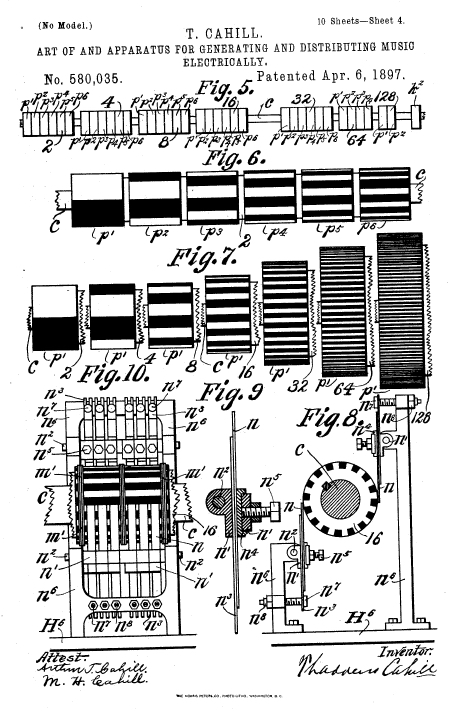

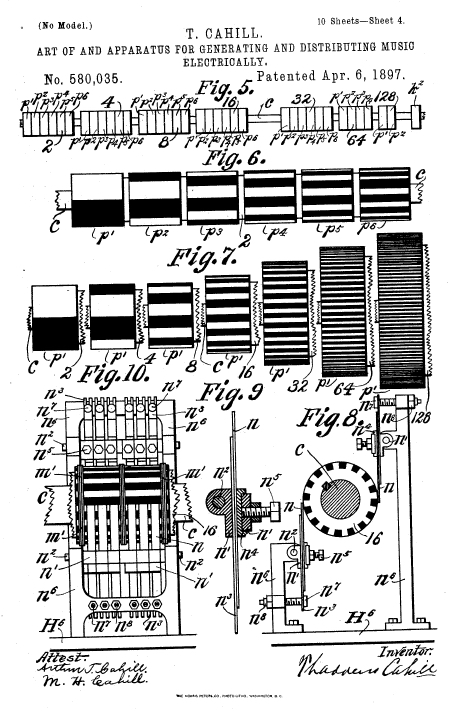

With amplifiers not yet invented, the phone receiver was still the only available technology that could make electrical sounds audible. Rather than use an oscillating circuit, the Telharmonium implemented an early form of additive synthesis via mechanical means using tonewheels, an apparatus that generates musical notes, and alternators, a device that turns mechanical movement into electricity.

Among his other legacies, Thaddeus Cahill is credited with coining the phrase “synthesizer” for describing his instrument, which was patented in 1897. Five years later he founded the New England Electric Music Company with two partners, but it wasn’t until 1906 when the Telharmonium, or Dynamaphone as it was also called, was first demonstrated. The instrument was a true boat anchor.

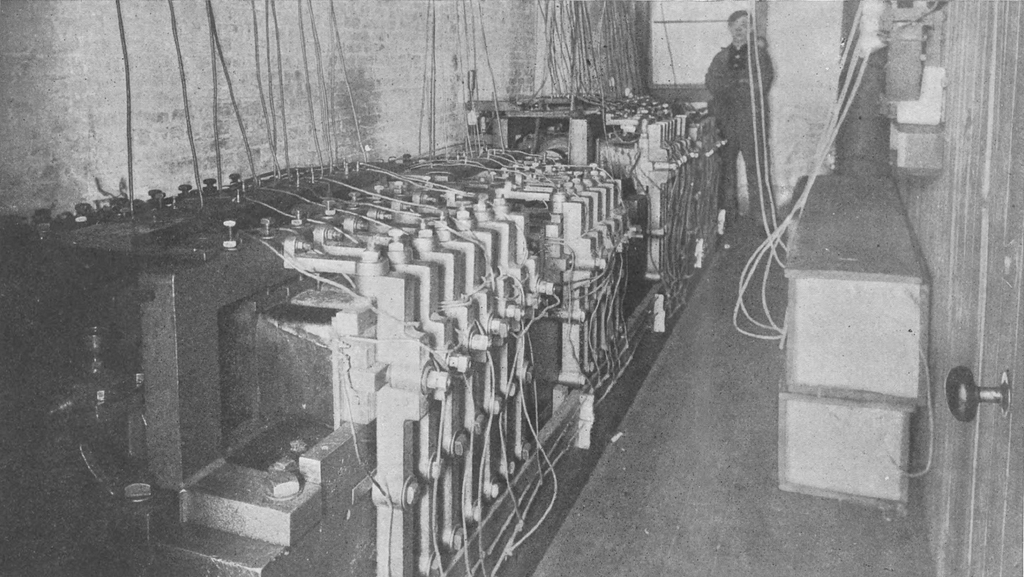

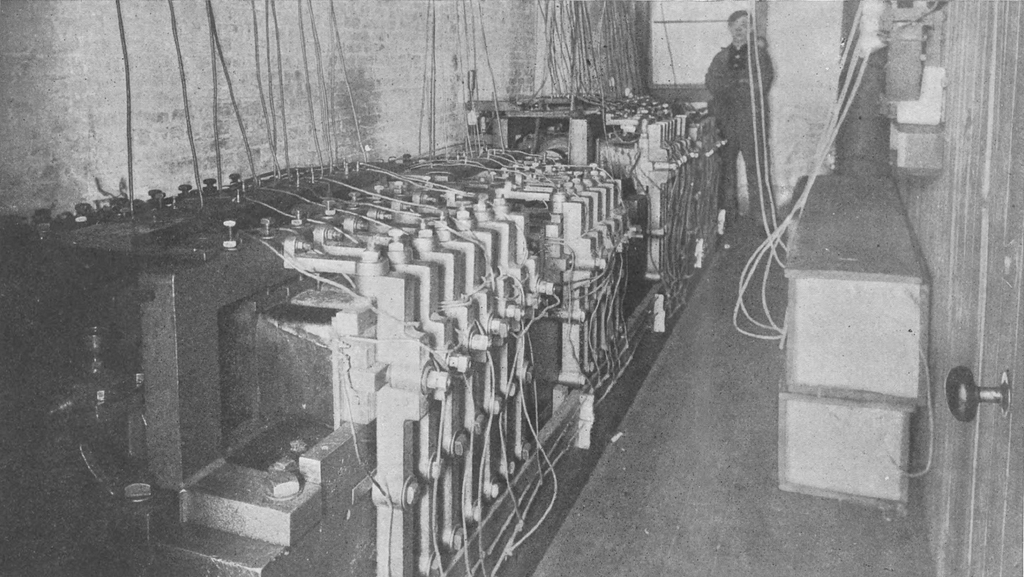

The Mark I version weighed in at a hefty seven tons and could be considered light compared to the Mark II and III, which weighed around 200 tons and took up thirty train box cars when shipped to New York for assembly in what Cahill called his Music Plant. Featuring a sixty foot chassis and 145 rotors, with each rotor producing a pitch, the instrument looked like a power generator and took up an entire floor on 39th Street and Broadway in New York City. The machine itself put out 670 kilowatts of power and required massive energy inputs. The sound of the electrical hum and machinery in the Music Plant alone might be enough to send noise music fans into a state of rapturous ecstasy.

One floor up from the instrument was Telharmonic Hall, a concert space where the Telharmonium was controlled and played. Two to four musicians could sit at the controls to play inside the listening hall. It was a unique arrangement of four keyboard banks each with eighty-four keys. Before the minimalist composers La Monte Young and Terry Riley brought it back into the fold of Western music in the 1960s, it was possible to play the Telharmonium using the tuning style of “just intonation.”

Just intonation differs from equal temperament—and was developed for keyboard instruments so that they could be played in any scale or key—in that it occurs naturally as a series of overtones where all the notes in a scale are related by rational numbers. Through additive synthesis, and the ability to control timbre, harmonics, and volume, the Telharmonium was extremely flexible in its sound, if cumbersome in its sprawling apparatus.

Though there was no channel separation, the Telharmonic Hall was fitted with eight telephone receivers augmented with paper horns to amplify the sound, which were arrayed behind ferns, columns, and furniture.

An electrician at the company suggested splicing the current from the Telharmonium into the electric arc lamps hanging from the ceiling, which then resonated at the same audible frequency as was being played to create a “singing arc.” The Telharmonium could also be piped to any phone number connected to the AT&T system.

Engineer Thomas Commerford Martin described the new sounds of the Telharmonium as an alliance of electricity with music, writing that Cahill had “devised a mechanism which throws on the circuits, manipulated by the performer at the central keyboard, the electrical current waves that, received by the telephone diaphragm at any one of ten thousand subscribers’ stations, produce musical sounds of unprecedented clearness, sweetness, and purity.”

Thaddeus Cahill had ambitious plans for his Telharmony -the kind of music played on a Telharmonium. He advocated that a form of “electric sleep-music” could be tapped at any time for the cure of modern nervous disorders. The electric drones could also be used to relieve boredom in the workplace.

Both of these uses are how many people use ambient music today. But his plans were not to bear fruit in the manner he thought. His massive instrument sometimes caused interference or crosstalk on the phone lines, with electronic music interrupting business and domestic conversations. It also required vast amounts of power. When vacuum tubes started to appear and in the 1920s, less expensive electronic instruments started being built. Then, with the advent of broadcast radio, many of these types of ventures ceased to be profitable. It is unfortunate that no known recordings of the Telharmonium exist.

In the 1930s, American engineer Laurens Hammond patented the electrical amplified organ. Hammond organs generated sound by creating an electric current from a metal tonewheel that rotated near an electromagnetic pickup. It was essentially a smaller and more economical version of Cahill’s Telharmonium, whose patent had not yet run out. It seems no coincidence then that when Cahill passed away in 1934, the Hammond organ went into production the following year.

Thaddeus Cahill’s work and his seminal place in the history of electronic music has since been recognized, even if the instrument itself had long ago been recycled for scrap metal.

The Radio Phonics Laboratory by Justin Patrick Moore is out now via Velocity Press.