On June 21, WEBO, the third installment in the Black Editions Archive series culled from the private tape library of drummer-percussionist Milford Graves, will be issued as a 3LP box set spotlighting previously unreleased performances from June 1991 held at the short-lived titular venue by the partnership of Graves, saxophonist Charles Gayle and bassist William Parker. The more than two hours of elevated interaction is especially timely, as tonight, Tuesday June 18, Parker will be honored with the Arts for Arts’ Lifetime Achievement award at the 2024 Vision Festival held at Roulette in Brooklyn.

Guitarist-composer-improviser-author Alan Licht’s terrific liner remembrance of attending the first night of these two astounding performances set off an avalanche of my own recollections from the same period regarding the three master musicians responsible; it feels right to arrange them together as part of this review.

Licht, a New York City resident prior to his attendance of the Webo concerts, cites night one as his first time seeing Parker and Graves playing live, adding that he’d listened to both on records. I was a frankly surprised by this statement, as NYC was very much in the thick (if not the specific focal point) of free jazz’s gradually resurgent profile during the period.

But upon reflection, Licht not witnessing Parker and Graves in performance prior to the Webo dates does make sense, as the free jazz rebloom at the dawn of the 1990s was very much a grassroots phenomenon (Licht adds that the Webo shows were promoted by flier, with no mention in The New York Times or Village Voice arts sections).

By 1991, then living (as I still do) in Northern VA, USA, I’d managed to soak up two recordings featuring Parker, both of them releases by pianist Cecil Taylor, Winged Serpent (Sliding Quadrants), a powerhouse large group session issued in 1985 by indie Soul Note, and In Florescence, an illuminating trio with Parker and bassist Greg Bendian put out on CD and cassette by A&M in ’89 as part of a trickle of major label activity, alongside discs by Don Cherry and Sun Ra, that Licht contrasts with the overall subterranean nature of free jazz in the late ’80s-early ’90s.

There were no contemporary recordings of Graves from this period, but I’d still tracked him down through the GRP/Impulse CD reissue of Albert Ayler’s Love Cry, which came out in 1991. But more importantly, I’d caught an extended glimpse of Graves and Parker in performance with saxophonist-bass clarinetist Peter Brötzmann as part of Mouthful of Sweat, a video compilation assembled by Mike McGonigal in connection with his small press magazine Chemical Imbalance, the tape put out by Atavistic (much later, the label responsible for the Unheard Music Series of avant-jazz reissues).

To describe the Mouthful of Sweat footage as revelatory is a severe understatement. Indeed, in emphasizing the power of uncut leaderless collective improvisation, that video clip captured at The Knitting Factory in the spring of 1988 was an utter jaw-dropper. For those desiring to take the big free jazz plunge in 2024, the contents of WEBO will do the same many times over.

In his own wonderful liner statement for WEBO, Parker makes it plain that his trios with Graves, whether completed with Gayle or Brötzmann or saxophonist Kidd Jordan, were all collective groups. Graves is emphatic in communicating the spontaneity of the meetings directly to the audience after the Mouthful of Sweet improv and also on WEBO, following two 20-minute improv explosions and a much shorter but equally incendiary piece integrating vocals, crashing cymbals, arco bass, a whistle, and the upper register wailings of Gayle.

If there is no hierarchy in the realization of the creative gush, then the equality should extend to the presentation. Interestingly, Licht recalls that Graves was “louder in the room” on the night he attended but that this discrepancy is balanced out in the mix of the release, which as Licht also states, situates Gayle in the left side, Graves in the middle, and Parker on the left (listening on headphones really brings this positioning to the fore).

Although Gayle had begun recording only recently at the time of this performance, Licht details how the saxophonist (more accurately multi-instrumentalist), long-based and playing upstate in Buffalo, was a true contemporary of Graves and Parker. At the point of the Webo performances Gayle had only three recordings released, one by his quartet, Always Born in 1988, and two by his trio, Spirits Before and Homeless in ’88 and ’89 respectively, all issued by the Swedish label Silkheart.

I’d read about these releases in Forced Exposure magazine, which was integral to what I’ll call the restlessly curious punk pipeline of the late ’80s (Chemical Imbalance and Mouthful of Sweat were also part of this impulse), but my attempts to order copies of Gayle’s Silkheart stuff proved futile. By this point, Licht had witnessed Gayle in performance many times, partly because The Knitting Factory had given him a Monday night residency during the period.

Repent, released in 1992 by Knitting Factory Works (and my introduction to Gayle’s music), was a direct outgrowth of that residency, recorded on January 13 and March 2 of 1992, both Mondays. The Gayle of Repent is very much the Gayle on WEBO, but with a crucial difference. On Repent, Gayle is clearly the leader (the same is true of the Silkheart releases, even with veteran saxophonist John Tchicai in the group for Always Born).

Across WEBO’s six sides, the leaderlessness is a consistent reality and a source of the release’s great power, even as there is a graceful ebb and flow to the dialogue. Licht further differentiates between the Knitting Factory groups and the Webo performances by designating the latter as Gayle’s public debut with a “world-class rhythm section.”

This might read as Licht throwing shade on the players who worked with Gayle on those nights at The Knitting Factory, namely bassists Vattel Cherry or Hilliard Greene and drummers Dave Pleasant or Michael Wimberly, but the crucial distinction is made that they were all younger musicians (Gayle was over 50 at this point), all gaining experience (Greene and Wimberley are still active) as Gayle worked to firmly establish himself on the scene. Having played in the subways and streets of NYC, the album title Homeless depicted a harsh reality.

Gayle was an unfailingly enigmatic figure throughout his life as a musician, but an additional layer of mysteriousness surrounded him early (his picture in Forced Exposure by photographer Michael Macioce really added to this aura). That he would form a bond with Graves and Parker, two individuals who’d refused to compromise as jazz made its big swing toward conservatism, can in retrospect seem like it was inevitable. That the music from the Webo nights wasn’t promptly released reinforces that the audience for it existed outside of the standard jazz avenues.

That punk pipeline was real. Gayle, playing drums, replaced guitarist Licht in Blue Humans, the group formed by guitarist Rudolph Grey at the dawn of the ’80s that straddled the no wave, avant-jazz and noise pillars in the city’s underground architecture. Had the music on WEBO been issued at the time of its creation, it surely would’ve been through independent channels, and it would’ve made a big splash, but those buying would’ve just as likely had an underground rock background as been jazz fans unhappy with the era’s neo-trad dominance.

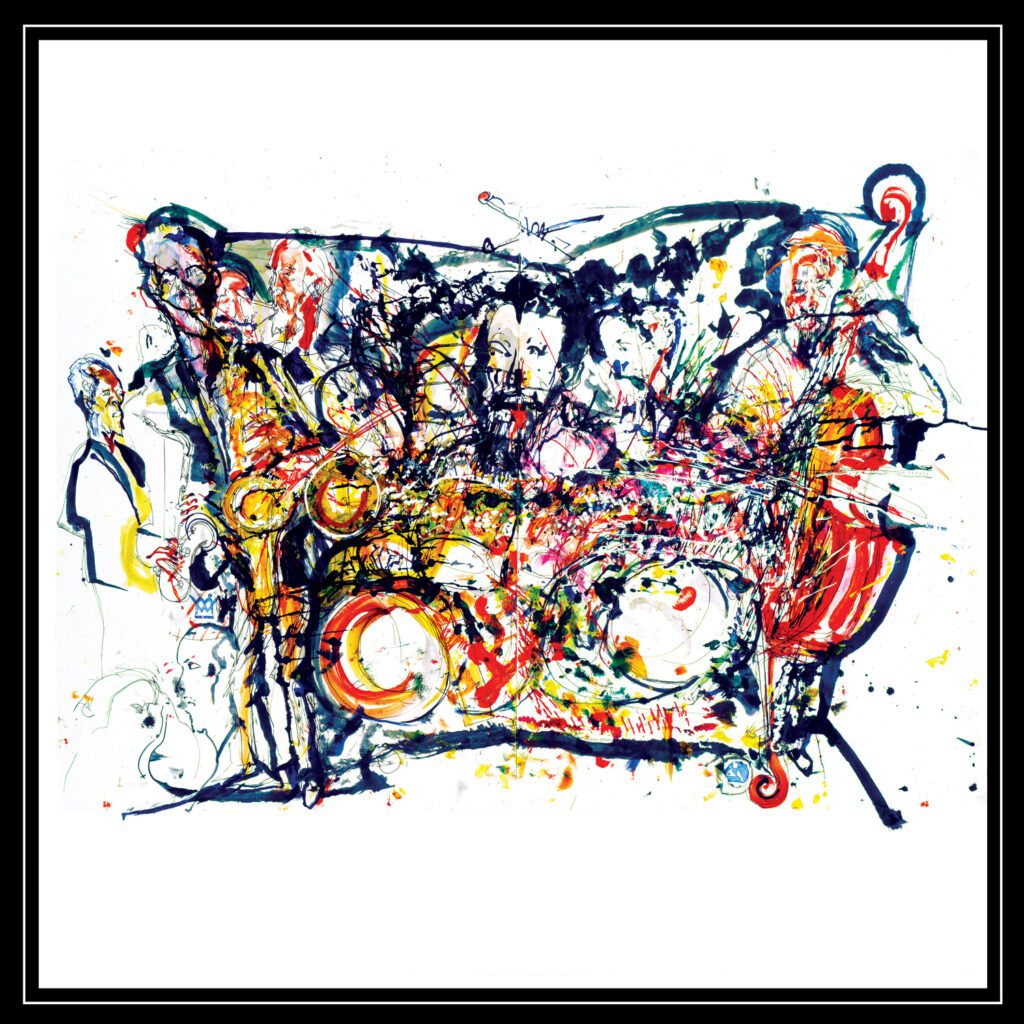

And yet, WEBO captures a vitally important part of jazz history, underscoring that the music thrives through the combination of dedication to the art (practice, making the gigs, practice, fostering community, practice) and embracing creative risk (never do the sparks of beauty truly fly by playing it safe). The cover painting by Jeff Schlanger – musicWitness, made June 8 1991 at Webo as the band hit its ecstatic peaks, is truly representative of free jazz’s enduring spirit.

WEBO solidifies Gayle, Graves, and Parker as a magnificent group no longer lost in the mythic folds of time, the set combining with Children of the Forest (unveiling Graves with Arthur Doyle and Hugh Glover) and Historic Music Past Tense Future (documenting a 2002 performance by Graves with Brötzmann and Parker) to position the Black Editions Archive amongst the very finest of contemporary reissue initiatives.

GRADED ON A CURVE:

A+