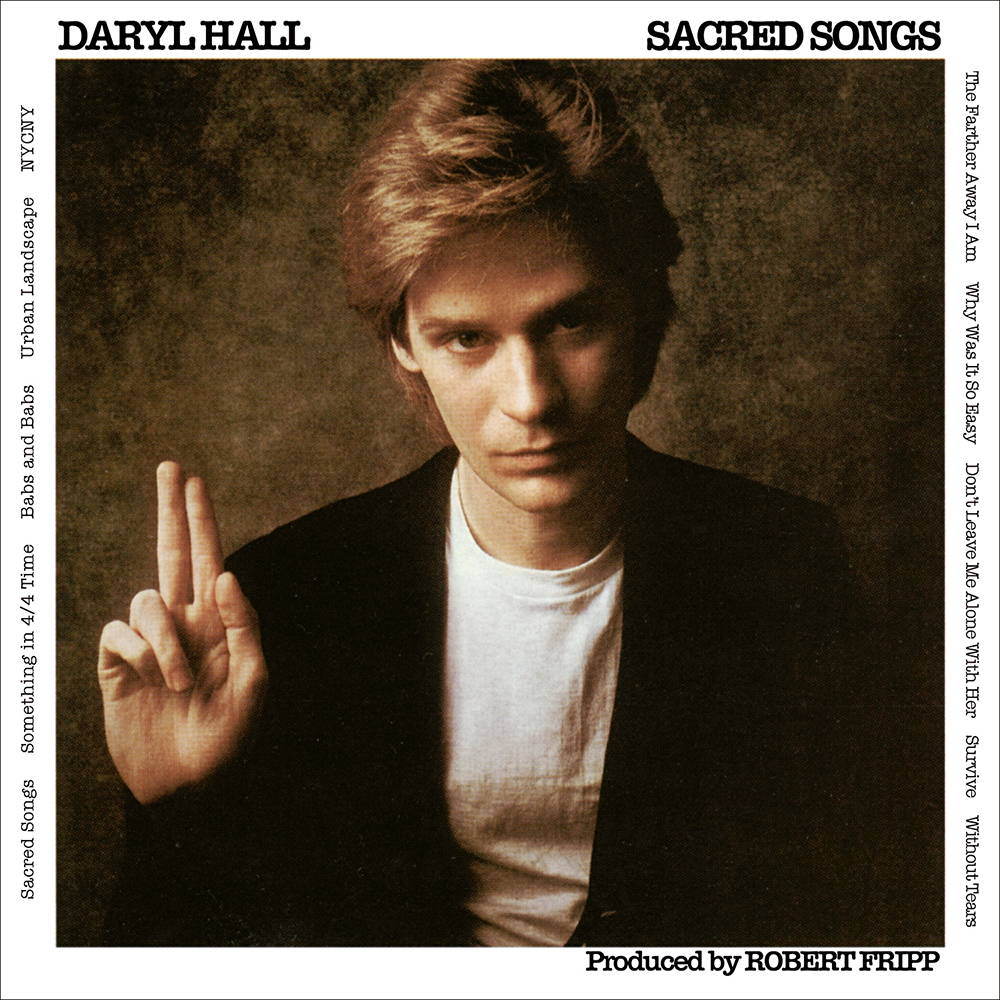

Celebrating Daryl Hall on his 78th birthday. —Ed.

While by no means an unknown work, it also seems fair to say that Daryl Hall’s first solo LP Sacred Songs gets nowhere near enough retrospective attention. This is mainly due to the inclusion of what many might consider to be an odd associate (at best) or an irreconcilable collaborator (at worst) in art-rock maestro Robert Fripp. Blue-eyed soul meets Frippertronics? Yes, indeed.

But folks who know Fripp’s contributions to Blondie’s Parallel Lines and especially Bowie’s “Heroes” have surely already comprehended that there’s more to the guy’s output than just King Crimson and (No Pussyfooting). And any fan of Hall & Oates that’s travelled back in their discography to their Atlantic Records period has been greeted with the unusual doozy that is Abandoned Luncheonette.

That 1973 album, their second after the pleasant but far from earth shattering debut Whole Oats, can be aptly described as a particularly ripe example of the commercial ambition of its decade. Not only does it include what’s maybe their best single, the sleeper 1976 hit “She’s Gone,” but the record’s second side heads into all kinds of unexpected areas, including the well-integrated use of electric violin on “Lady Rain” and even some fiddle and banjo on the seven minute album closer “Everytime I Look At You.”

It’d be the incorrect impression if readers somehow surmised that Abandoned Luncheonette was representative of this writer’s typical listening diet, but it is an LP that’s really quite splendid for those extremely muggy days where it’s advisable to not do much more than sit on the porch, sip lemonade, and sweat profusely, either alone or in tandem or with a smartly-chosen partner in perspiration. Plus, I dig it more than War Babies, the duo’s third and final record for Atlantic, a collection that found them messing around with a tougher rock based sound.

War Babies featured production by Todd Rundgren and the musical contribution of his band of the period Utopia. This fact is undoubtedly a big part of why that LP impresses me far less than does its predecessor. After the top-notch Something/Anything? Rundgren’s work seldom resonated much with these ears, and my unshakeable impression of Utopia is that they were admirable in concept but underwhelming in execution. I’m positive that War Babies has its fans even if I can’t give the disc more than the very faint praise of being “not unlistenable.”

But Utopia was Rundgren’s indulgence in a progressive rock state of affairs, which makes his and their appearance on War Babies an interesting antecedent for the far more fruitful matchup of Hall and Fripp via Sacred Songs. Before they could get there however, Hall had to deal with the noodle-pated “guidance” of the rapidly faltering record industry. Their Atlantic contract completed, Hall & Oates signed to RCA, and by the release of ‘76’s Bigger Than Both of Us, where the label insisted on using studio musicians instead of the pair’s actual working band, Hall was feeling the creative pinch.

Or so the story goes, and I’ve no reason not to believe it. Fripp and Hall had reportedly first met in 1974 and after the former’s liquidation of King Crimson and eventual relocation to New York City in ’77 it became possible for he and the latter to make good on their shared desire to work together. Serious music fans live for just these kinds of circumstances. Record company bean counters, not so much.

And if this all sounds a little (or a lot) dubious for non-fans of Hall & Oates, at least please consider that the duo’s success as an R&B-inspired pop-chart juggernaut completely lacked any straining for authenticity. Circa the ‘70s they can perhaps be considered as inheritors of the sincere crossover tradition of The Righteous Brothers blended with the stylistic restlessness of say the young Stevie Winwood. In short, to judge them only on the hits is a mistake.

The recording of Sacred Songs was completed in 1977, but the LP wasn’t released until 1980, where it sold quite respectably, peaking at #58 on the album charts. RCA’s reasoning for the delay was that the record wasn’t commercial. Actually hearing the ten songs that comprise the original LP configuration makes it readily apparent just how off base that logic was. Instead, the nature of the label’s problem with Sacred Songs gradually becomes clear; it simply didn’t sound enough like Hall & Oates.

The opening title track has a feel that’s very remindful of the back-to-basics rocking exemplified during this same period by cats like Dave Edmunds, Nick Lowe, and Graham Parker. It features some excellent punchy guitar in tandem with Hall’s very fine, slightly New Orleanian keyboards. This is followed with “Something in 4/4 Time,” and it’s here that the depth of Hall’s and Fripp’s collab really begins to take shape. The tune, as solid a slice of uptempo late-‘70s pop as Hall ever conjured up, holds in its mid-section a short guitar passage that’s unmistakably the work of Fripp.

And the kicker is how well it succeeds; Fripp’s playing could’ve very easily just been grafted onto the song in an attempt to surgically enhance Hall’s perfectly fine pop songwriting, but it quickly becomes obvious that much time and thought went into this project. And “Babs and Babs,” a highly rewarding and nearly eight minute mixture of the personalities of both principals, really amplifies the collaborative energies of the whole project. That the song drifts right into “Urban Landscape,” a sweet slice of undiluted Frippertronics, might lead some to the conclusion that Sacred Songs is as much a Fripp album as it is one by Hall.

And there’s certainly some truth to this assumption, but the reality is that Hall is the sole writer of all but two of this album’s tracks; “Urban Landscape” belongs to Fripp alone and the raucous, stomping rocker “NYCNY” is credited to both of them. It bears noting that from within his own oeuvre, Fripp considered this album as a part of a trilogy with his work as producer on Peter Gabriel’s second solo LP and his own 1980 solo debut Exposure. So there are all sorts of inroads to the goodness of Sacred Songs.

The second side opens with “The Farther Away I Am,” which actually manages to blend the sonic textures of (No Pussyfooting) with the kind of weary soul-mope that was one aspect of Hall’s calling-card. The following track “Why Was It So Easy” falls closest to the work of Hall & Oates. It’s a long study in love-burn sass that would’ve surely turned up on a subsequent recording by the duo (or a future Hall solo rec) had Sacred Songs somehow remained in the can.

“Don’t Leave Me Alone with Her” returns to the direct delivery of the title-cut, though it also includes a fine rocking solo from Fripp along with a sly fake-out fade-out. The extended grooving of “Survive” continues the quality, again showing-off Hall’s skills as a pianist, and the brief balladry of “Without Tears” wraps things up quite nicely, with Fripp’s electronic layers giving the cut an added warm dimension.

Compact-disc reissues of Sacred Songs included two bonus tracks, “North Star” and “You Burn Me Up I’m a Cigarette,” both of which appear on Fripp’s Exposure album. These cuts are certainly worth hearing (though primarily in the context of the quite good Fripp LP), but the meat of the matter is the ten cuts that comprise the original LP issue. Those songs accumulate into a statement that far exceeds mere curiosity, achieving a superb level of expression that should’ve found a much larger audience.

That is, I tend to agree with Fripp when he states that if this album had been released in the tumultuous year of ’77, it would’ve likely presented Hall to a wider audience as not just another very good pop songwriter and vocalist but as a groundbreaker as well. But just because RCA stymied Hall and Fripp and in turn screwed the world out of an enticing alternate possibility, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t celebrate the artistic success of Sacred Songs. It’s a swell antidote to the often overwhelming insubstantiality of so much mainstream pop.

GRADED ON A CURVE

A-