Celebrating Dion on his 85th birthday. —Ed.

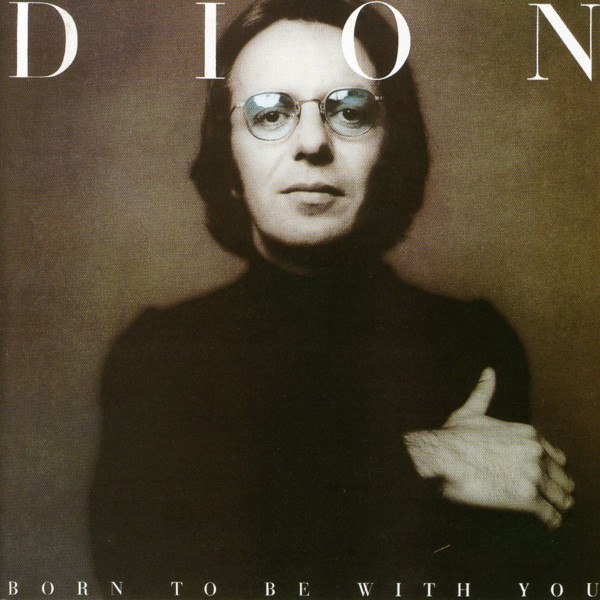

Poor Dion DiMucci. In 1975 the singer-songwriter from the Bronx—still seeking to recapture the fame he achieved in the late 1950s and early ’60s with vocal group The Belmonts and as the solo artist who gave us “The Wanderer” and “Runaround Sue”—made the same mistake so many musicians seem to make: he decided to hire fellow Bronxite Phil Spector to produce his album. Fortunately Spector—a stick of unstable human dynamite on a good day—didn’t shoot Dion, or so much as brandish a gun at him or even give him a wedgie, as he did the Ronettes. But Spector was his normal—which is to say volatilely abnormal—self, and the sessions were chaotic, to say the least.

Dion’s career trajectory is complex, zig-zagging improbably all over the place like the Kennedy Assassination’s Magic Bullet. He began with The Belmonts, which made him famous and almost killed him on the frigid evening of February 3, 1959, when Dion—travelling with the Belmonts as part of the Winter Dance Party tour—declined for financial reasons to board the infamous Beechcraft Bonanza that crashed near Clear Lake, Iowa, killing fellow tour members Buddy Holly, Richie Valens, and The Big Bopper. In 1960 Dion went solo, and more hits followed. Then he fell prey to heroin addiction, and his style of music became instantly antiquated the moment the British invaded.

DiMucci spent several years in the pop wilderness, experimenting without much pop success with rock and classic blues. But—and here we are, back at the Kennedy Assassination and the Magic Bullet again—in 1968 Dion covered Dick Holler’s “Abraham, Martin & John,” not long after having a profound spiritual experience and giving up heroin. The song became a hit and put him back on the musical map. It also helped establish him as a mature artist, rather than a teen idol. Over the next several years Dion recorded a series of excellent LPs, including Born to Be With You.

Dion’s reputation as Bard of New York City’s mean streets has won him comparisons to the late Lou Reed, but they’re very different creatures. Dion is all heart and soul, a romantic, while Reed, who was a genius, was all brain. Reed’s was a cooler, more ironic stance than Dion’s; detachment might as well have been Lou’s middle name. Dion, on the other hand, never fails to exhibit a winning warmth, and on songs like “Your Own Backyard” he demonstrates a compassion and empathy that Reed—despite his myriad merits—simply didn’t have in him.

As for Born to Be With You, Dion’s disowning it just goes to show that sometimes artists are the worst judges of their own work. And as for its being “funeral music,” I don’t hear it. Born to Be With You is no Berlin. It has a big, soulful sound—of course, duh, Phil Spector produced it—that I find moving and often joyous. In my opinion every song (with the possible exception of “Make the Woman Love Me”) works, including the oddball choice of “(He’s Got) The Whole World in His Hands.”

Both the title track and “Only You Know” open with long, moving instrumental passages. This isn’t funeral music; the opening to the ballad “Born to Be With You”—which reminds me a bit of Spiritualized, whose Jason Pierce is a big fan of the LP—moves prettily along, a sax and tambourine joining in along the way, until Dion comes in and swings until he reaches the wonderful chorus (“Little girl, I was born, born, born, born/To be with you.”) The sax plays a slow, funky solo, and the strings are understated, and the drums are great, but Dion is always at front and center, bending his vocals and throwing in ad-libs and even scatting some at the end. The instrumental that opens “Only You Know” is harder hitting, and features drums, some understated horns, and that ever-present tambourine. As for Dion, he throws everything he has into the song, hitting his ecstatic high notes while Spector’s Wall of Sound is as formidable as the one that used to bisect Berlin.

I can hardly fathom it, but “(He’s Got) The Whole World in His Hands” is great, thanks to the unique arrangement worked out by Dion and Spector. The melody is similar but all souled up, and they chose to break up the original’s smooth flow, so that what you get is a choppier, hipper arrangement. Instead of singing “He’s got the whole world in his hands” in one smooth flow Dion sings, “He’s got the whole world… in his hands.” It works amazingly well, and Spector provides the perfect instrumentation, including those big drums and female backup singers galore and strings. Meanwhile Dion is in powerful voice, and I love it when he sings, “He got the little bitty, little bitty/Baby people/In his hands.”

As for the slow, romantic “Make the Woman Love Me,” it’s my least favorite track on the LP, because I find the melody to be undistinguished. But it has its charms, the chief of which are Dion’s vocals and the chorus. Spector’s production is up to scratch too. And there’s something to be said for the opening lines: “Lord I know I haven’t asked for much/In such a long, long time/Not since that brand new pair of Levis/Back when I was 8 or 9.” Which leads up to Dion telling the Lord he knows he’s busy, but if “you ever find yourself with a minute or two/Won’t you please make the woman love me?”

“New York City Song”—one of the two tracks on the LP not produced by Spector—is a lovely, nostalgic, and sad eulogy to the Big Apple. Its sound is more stripped down, although there are some strings and lush backing vocals, and Donovan’s voice aches as he sings, “That’s the year my dream died/In New York City/That’s the year I had to leave that town.” He adds, “There will always be a little New York City in my heart,” and listening to it you can hear the gulf that separates a (pseudo) tough guy like Lou Reed from Dion DiMucci. The latter is all heartache and tenderness, and while I’ll always love (hate) Reed, he just couldn’t do heartbreak. Because to pull it off requires heart, something that even “Sweet Jane” and “Pale Blue Eyes” lack.

“Good Lovin’ Man” is a mover and shaker and one fabulous tune, with oodles of female backing vocals and Dion singing up one soulful storm about how he’s a “a New York good lovin’ man.” There’s a cool guitar riff, yet more tambourine, and a cool sax towards the end when Dion sings, “I’m ready, steady/Steady like you rock me/Ain’t nobody like I am.” This one hearkens back to a lost time; it sounds like it could have been recorded in the mid-sixties, which is cool—instant oldie, just add water. As for “In and Out of the Shadows,” it boasts big horns, chimes, and a wailing guitar that comes and goes. For some reason this one brings late-era John Lennon to mind, although it’s superior to anything produced by the ersatz stay-at-home daddy. It’s not the beautiful melody; perhaps it’s that guitar. Anyway, Dion wails his way through it, hanging on to the ends of verses seemingly forever, his vocals more urgent than on any of the LP’s other cuts. There’s a big horn and string interlude, followed by Dion singing, “Oh mama, that’s me/In the middle of a dream/Tell me, what does it mean/For you or for anybody.” And then there’s the wonderful chorus (“In and out/Of the shadows/There ain’t no place that you can hide/But you can try… /Try to be humble in your pride.”) And then those horns and strings return, and the song fades out.

But the LP highlight—which is quite possibly Dion’s masterpiece and without a doubt the best tune ever written about going through heroin addiction and coming out the other side—is “Your Own Backyard.” I’ve always been undecided as to which I love more, Dion’s version or Mott the Hoople’s 1971 cover on Brain Capers. But it don’t matter, cuz I love ‘em both. Produced by Phil Gernhard, the redemptive “Your Own Backyard” opens with an acoustic guitar and Dion singing in a friendly and conversational tone, “I’ve been sittin’ here thinkin’/About when I started in drinkin’/I went on the dope surely to change my life/Oooooh.” The instrumentation is simple (guitar, bass, a very Dylanesque organ, drums) and the song has propulsion, and as for Dion’s vocals, they may be conversational but they exude pure joy and gratitude at having escaped the nightmare of junk.

Dion tells the story of his addiction and recovery with a warmth that extends to his audience, as when he sings, “Believe me you’re all beautiful people just the way you are/Tell me, what has that stuff done for you so far?” His is the same old refrain, familiar to any ex-junkie: “Many a time/I swore up and down/I didn’t need any of this junk that was goin’ round/I can quit, let me finish what I got/After all this stuff sure costs a lot/Then I’ll get my feet back on the ground.” But quit he finally does, and I love it when he sings, “You know I’m still as crazy as a loon/Even though I don’t go out and cop a spoon/But thank the good Lord God I had enough.” Just as I love the ending, when he sings, “I can do anything that I wanna do/I do it straight I do it so much better too/But it’s gotta start in your own backyard/I says its gotta start in your own backyard/You know everybody has their own beautiful backyard/You might have oil wells in your own backyard/Yaaaaah.” What can I say about this song other than it’s the shit when it comes to giving up the shit, and you owe it to yourself to check it out.

Dion may not be the greatest rocker who ever lived—I’ve never cared much for his teen idol stuff, and his later work, while adventurous, is uneven. If you ask me, Born to Be With You, 1969’s Wonder Where I’m Bound, and 1989’s Yo Frankie are the must-have Dion LPs. But man, does the guy have spirit. Neil Young may have sung, “Even Richard Nixon has got soul,” but some souls are bigger than others, and Dion—teen idol, junkie, survivor, and rock’n’roller—has got a bigger soul than almost anybody I know.

The proof is in this album and especially “Your Own Backyard,” a better cautionary tale about drugs than Young’s “Tired Eyes” and “The Needle and the Damage Done,” Johnny Winter’s “Still Alive and Well,” James Brown’s “King Heroin,” the Velvet Underground’s “Heroin,” Buffalo Springfield’s “Burned,” Bert Jansch’s “Needle of Death,” and even Donny Osmond’s “(Damn the Man) Hooked on Screaming Yellow Zonkers Again.” To name just a few. Dion went to Hell and returned to tell the tale, as plenty of people have done. But his telling is easily the most compassionate and moving, and for that I will always love the guy. And talk about your survivors—he lived through Phil Spector too!

GRADED ON A CURVE:

A