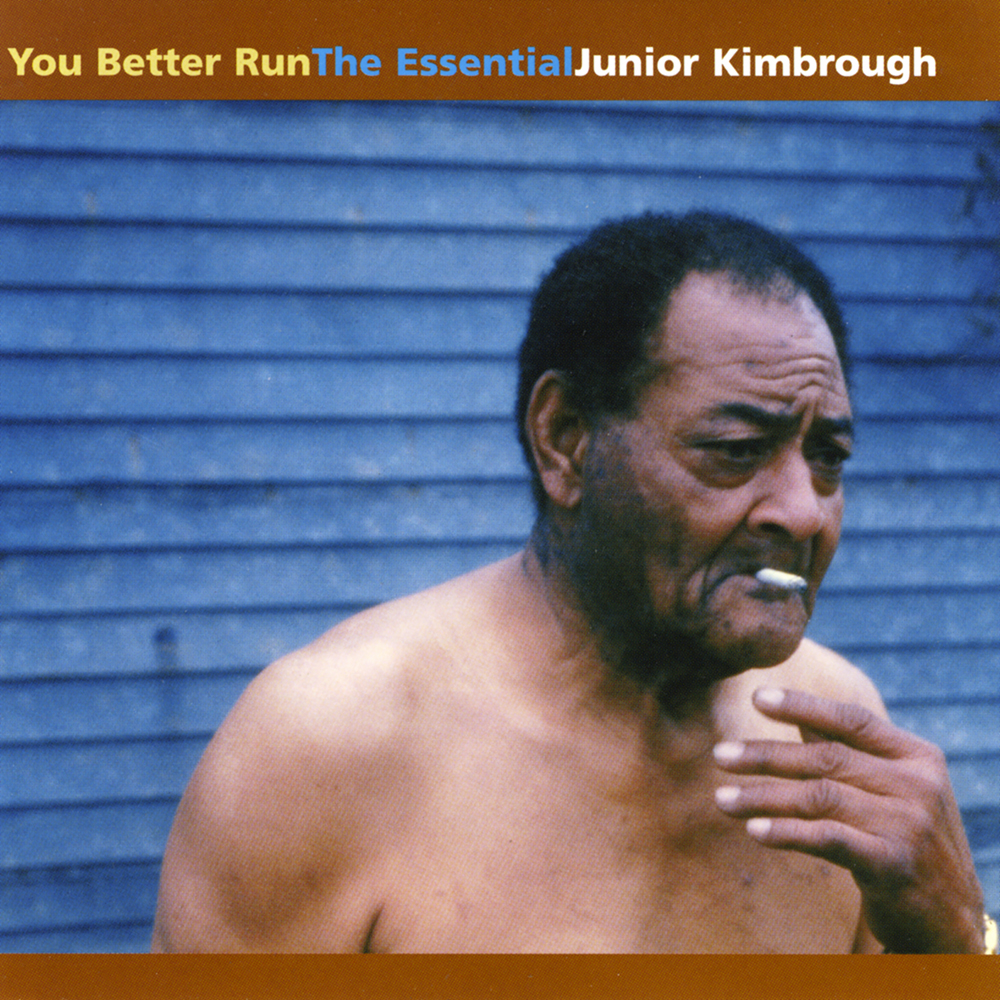

Before we get down to the nitty gritty on why the late Junior Kimbrough is one of the few blues musicians I can listen to, take a gander at that album cover. It tells you everything you need to know about the Mississippi hill country blues guitar legend.

What it tells you is what we have here is a man who cares deeply about his personal appearance. Who knows how to dress for success. Style is everything to this guy. He’s a dude. Okay, what it actually tells you is that here is a guy who doesn’t give a shit. Why, he can’t even be bothered to put on a shirt, and Robert Plant he ain’t. (On 1992’s All Night Long, he is wearing a shirt, but it’s a godawful pink dress shirt he probably paid two bucks for at Goodwill.) Who slaps a picture like that on their own album cover? What’s he trying to tell us? I’m the type of guy whose idea of a good time is going to the town dump to drink beer and shoot rats?

And I like that about Junior Kimbrough. It speaks to a complete indifference to commercial considerations, and to a lack of personal ambition that extended to his actual recording career. Kimbrough first walked into a recording studio in Memphis, Tennessee in 1966 to record for Goldwax Records. He was in his mid-thirties—hardly a young man in a hurry to make his mark. The album he recorded there collected dust until 2009. The head of Goldwax Records (the wonderfully named Quinton Claunch) thought Kimbrough sounded too country.

Kimbrough didn’t seem to much care. What he did care about was playing live (often at house parties) and operating juke joints. And fathering children—he had thirty-six in total, ten more than he’d need to start his own professional baseball team! As a result he released only a small handful of songs until 1992, when he released All Night Long—some twenty-six years after those first sessions in Memphis. He recorded it at Junior’s Place, a juke joint he operated outside Holly Springs, Mississippi, some nine miles from the town where he’d been born and less than forty miles from the stomping grounds of R.L. Burnside, one of the few other blues musicians I can stomach. Junior Kimbrough was not a rambling man.

But Kimbrough had traveled a long way on his guitar. All the way to Africa (which I’ll get around to) in fact. While most of his blues contemporaries were conjuring lightning out of plain electricity and performing whiplash miracles, he’d developed a style that was as unflashy as it was unique. His raw take on the hill country blues involved a steady drone played with his thumb on the bass strings, which he syncopated with his midrange melodies. The word “modal” gets tossed around a lot. As does the word “hypnotic.” I prefer the latter (I don’t even know what “modal” means!).

Kimbrough’s playing does not “wow” you—it puts you in a trance. Fellow Mississippi bluesman and former Kimbrough bassist Eric Deaton made an analogy to the music of the Fula people of West Africa (although you’ll find them in plenty of other locales). He wasn’t inspired by their music—Kimbrough wasn’t the type to sit around listening to Folkways albums. He came up with his style—which rumbles along, unstoppable, like a locomotive powered by boilermakers—all by his lonesome.

He had influences—nobody summons a style out of thin air, whether it be the air of South Side Chicago, the swamps of Southwest Louisiana, or Marshall, County, Mississippi—in Lighnin’ Hopkins and Mississippi Fred McDowell. But they were just departure points on a journey that led him to a place that wasn’t on any musical map. He doesn’t sound like them. In fact, there’s an almost archaic quality to his playing that could lead you to mistakenly assume he predates them.

Blues guitarists tend to be pyrotechnicians. But fireworks weren’t Kimbrough’s style. His music reminds me of the old Appalachian folk song about the mole in the ground, rooting the mountain down. Moles aren’t flashy. They don’t show off. They dig. And that’s the way with Kimbrough. He doesn’t take flight. He’s not a goddamn bird. There is no colorful plumage. You put the needle down and here comes this almost subterranean rumble. And he sings like he plays—all gut and cigarettes. His songs shake mountains down.

On most of the songs on the 2002 Fat Possum Records compilation You Better Run: The Essential Junior Kimbrough the guitarist/vocalist is backed by Gary Burnside (R.L. Burnside’s brother) on bass and Kenny Malone (Kimbrough’s son) on drums, although Gary Beavers plays bass on some tracks. Alabama slide guitarist Kenny Brown (who R.L. Burnside liked to call his “white son”) also appears.

On opener “Release Me” (which Junior also released under the title “I Feel Good Again”) he’s joined by rockabilly legend Charlie Feathers—a Holly Springs native—who throws in on acoustic guitar and tosses in some asides here and there. The number’s almost sprightly by Kimbrough standards, and sounds brighter than usual thanks to that acoustic guitar. But the drone kicks in from his opening “Heeeeeeeeeeey” and never lets up.

“All Night Long” is archetypal Kimbrough–he does the black snake moan above a muscular groove powered by Malone’s drum stomp and Burnside’s surprisingly fluid bass. Meanwhile, he produces a drone on his guitar that will put you in a hypnotic state so deep you’ll be grateful he doesn’t tell you to start clucking like a chicken because you would! That goes double for the doleful “Done Got Old,” on which he plays all by his lonesome, giving you as clear a view of what he does as you’ll ever get. And if that isn’t the best title ever for a blues song I don’t know what is. My baby done left me? Big whoop! The guy had thirty-six children! He just went out and found a new one! I hope! Now growing old—that’s depressing!

But I take that back. “Most Things Haven’t Worked Out” is the best ever title for a blues song! It’s a rumbling and surprisingly funky instrumental with some deft soloing (and some up-front bass) guaranteed to get the juke joint jumping. “Keep on Braggin’” is all churning chug-a-lug, a remorseless barroom brawler that doesn’t float like a butterfly but just comes in close and won’t stop punching, that is until Kimbrough whips out a solo that stings like a bee. And “Keep on Braggin’” may as well be Muhammad Ali compared to the Joe Louis pummeling that is “Tramp,” on which Kimbrough talks over a grinding beat while Kenny Brown plays some truly fierce slide guitar.

“I’m Leaving You Baby” is as dead simple (just Kimbrough and his guitar) as it is eerie. There’s something wonderfully off about its gait—it brings to mind a Tennessee walker making its woozy way home after a hard night of drinking gin and juice. “Sad Days, Lonely Nights” kinda runs in place—it’s up-tempo but gets nowhere except into your head. Malone pounds mud while Kimbrough plays wild circles on the guitar, trying to escape the inexorable misery of his own life. The sun goes up, the sun goes down, and it makes no difference because it’s all a grim grind, and if that ain’t the blues what is?

“Meet Me in the City” has this beguiling little melody going for it, behind which Kimbrough’s vocals sounds less gruff than usual. It goes on and on, just Kimbrough playing that melody, and it’s all so basic and hypnotizing you won’t realize you’re drooling until it’s over. Then comes the king bastard drone of “You Better Run,” which is all about a man with a knife and how you’d better be fast or he’s gonna rape you. But what with that going-nowhere-fast beat it’s like you’re running in wet cement and things don’t look good, they don’t look good at all. And the lines “You don’t have to rape me, because I love you” are the scariest part of the whole damn song.

“Old Black Mattie” is a ramshackle Stagger Lee of a song that propels itself forward by means of a forceful lurching, like it could all fly apart but won’t because these fellas know exactly what they’re doing. As for live closer “Nobody but You” it’s got this great cartoon sneaky bass line over which Kimbrough lays down some really snaky guitar while singing like he’s some kind of Muzzippi hill prophet come down to give the worldly the bad news. While some guy in the crowd simply can’t contain himself. After which the master of ceremonies shuts things down by saying, “Play a little music while, uh, we bring on this little soul thing.” Wish I’d been there.

But I never got around, although I kinda did, to telling you why Junior Kimbrough is one of the few blues guitarists I can listen to. Well here goes: most of the other dudes are all flash and dazzle! They sound like they’re wearing thousand-dollar suits! Their guitars sound like they’re wearing thousand-dollar suits! Their virtuosity and showmanship and ability to play the guitar like they’ve spent the past forty years alone in the desert practicing forty-four hours a day bores me to tears! You know their names! And they’ve beget others, way more than thirty-six, white guys most of ‘em with names like Eric and Duane and Stevie Ray who also know their way around the neck of their guitars the way an old blind man knows every last dimple on his fat wife’s ass! It’s a cult of the musically prolix! I know a thousand chords and I’m gonna play every last one of them! In six seconds flat!

Junior Kimbrough was working at a whole other level. He wasn’t in it to bedazzle, sell the sizzle or knock you out of your sneakers. And he definitely wasn’t wearing a thousand-dollar suit. He wasn’t even wearing a shirt! For all I know he favored polyester trousers! He was working from the gut, from the muddy bottom where the true blues come from. He never showed off but he always showed up and he knew how to put a hurting on you. He had no time for flair. He was spawned by the Mississippi hills and he operated juke joints. You have to take straight razors away from angry men in such places, and I’ll bet you he did it without worrying about his hands.

GRADED ON A CURVE:

A