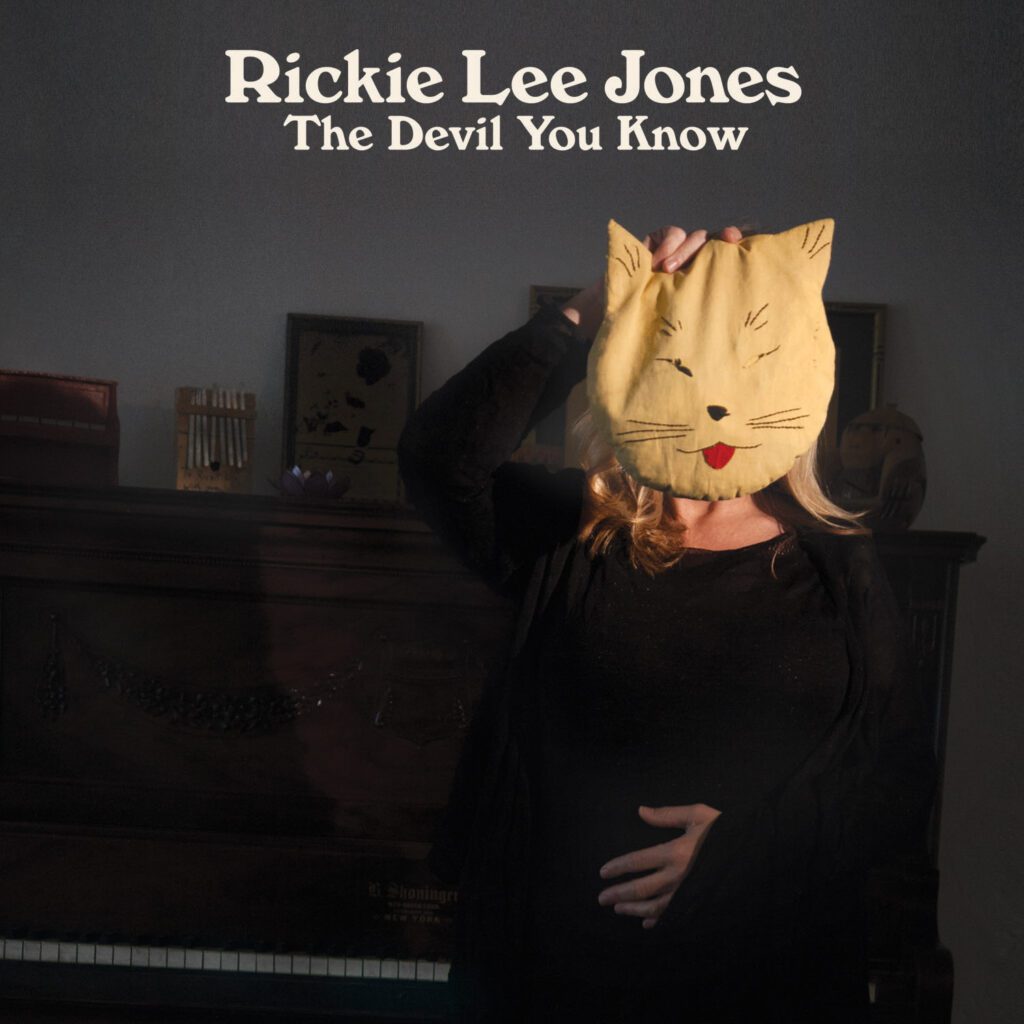

Celebrating Rickie Lee Jones on her 70th birthday. —Ed.

I’ve always had the same issue with Rickie Lee Jones as I do with Tom Waits; to wit, I can’t escape the sense that they’re beatniks escaped from a time capsule. There’s something atavistic about their sound; hearing it, it’s impossible to escape the eerie sensation that you’re sitting in a smoky and low-ceilinged Village club, the Kettle of Fish say, surrounded by beret-wearing hipsters in goatees, of the type who click their fingers instead of applaud.

Jones’ career took off with the release of her 1979 self-titled debut, which featured dozens of top-notch LA sessions players—to say nothing of Dr. John on piano and Randy Newman on synthesizers—and included the great “Chuck E.’s in Love.” Buoyed by a highly touted performance on Saturday Night Live, she soon found herself on the cover of the Rolling Stone, and her beret quickly became more famous than Joni Mitchell’s beret, which no doubt pissed off Mitchell’s beret to no end.

And she would likely have become a superstar had she not drifted inexorably jazzwards, a move that she found creatively fulfilling but didn’t win her many pop fans. Henceforth she toiled in the jazz-pop wilderness, moving to Europe where she battled with writer’s block. But she continued to record, moving from more mainstream projects to more avant-garde efforts, none of them wildly successful but most of them critically praised.

She’s performed lots of covers over the course of her long career, from David Bowie’s “Rebel Rebel” to Steely Dan’s “Show Biz Kids” to Traffic’s “Low Spark of High Heeled Boys.” But The Devil You Know is her first all-covers LP, and to say she desecrates some standards is an understatement. But with a single exception, she desecrates them to their benefit. The instrumental arrangements are sparse, sometimes just a piano, and Jones drags the songs slowly past your ears, which at first may irk but in the end captivates.

The LP opens with a bass leading to Jones’ somnambulistic, mumbling, quavering, but inexplicably effective take on the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil.” Producer Ben Harper plays some minimal guitar and percussion, while Jones whispers, warbles, groans, and sounds nothing like the strutting Satan of Mick Jagger. But in the end her vocals suck you in; you never know where she’s going next; even her “whoo hoos” (at which you can hear Harper in the background playing electric guitar) sound less triumphant than resigned. What you end up with is a Satan who sounds like he’s unbearably tired of the Satan business, but is condemned to carry on.

Her version of Neil Young’s “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” is one of the more fleshed-out tunes, and it is also the LP’s loveliest, a heartbreaker that will make you forget all about Uncle Neil’s version. Guitar, some organ, piano, and the barest of backing vocals give Jones the space she needs to slowly destroy you, if you’re hurting or have ever been hurt by a lover. Her take on Harper’s “Masterpiece” is incredibly slow and atmospheric, and reminds me a bit of Van Morrison in contemplative mode. Indeed, Morrison is the only vocalist who I can think of who would dare take such chances, and I would love to hear a duet between the two of them.

“The Weight” follows, just Jones and a piano, and she takes tightrope chances, fearlessly dragging the song out and deemphasizing the melody so that what you get is pure voice, the voice of a soul lost in legendary Nazareth, and just trying to find a place to put her burden down. Meanwhile, her take on the American folk song “St. James Infirmary,” that bummer of a tune about a hospital for venereal diseases, features some subtle guitar and drumming, and has Jones going from mournful to a shouting, “Let her go/Let her go/God bless her.” This one’s jazzier than the bulk of the tunes but no wonder; Louis Armstrong first made it famous in 1928. As for her take on Van Morrison’s “Comfort You,” its drag is even more than I can handle, and it’s the only tune on the LP I find tiresome.

David Lindley’s violin opens Tim Hardin’s “Reason to Believe,” which Rod Stewart made famous by recording it for his LP Every Picture Tells a Story. It’s a doleful number, with some beautiful violin and tasty guitar by Harper, and Jones’ phrasing is a wonder to behold, as she takes stylistic vocal leaps I can’t think of anyone else taking. She returns to the Rolling Stones to cover their “Play with Fire,” which opens with some whistling and rudimentary guitar, and which Jones kicks ass on. She does things with her phasing and modulation that are subtle but miraculous, and I’ll take her version over the Stones’ version any day.

She also returns to Stewart and Every Picture Tells a Story for “Seems Like a Long Time,” which she opens barely accompanied by acoustic guitar and on which she sings in a more or less traditional way at a more or less reasonably traditional pace. Then some tasty organ and guitar come in, and her vocals are unutterably lovely, especially as she reaches for the high notes at song’s end. She closes the album with Donovan’s beautiful if Dylanesque “Catch the Wind,” and she sounds elegiac as she sings, “I may as well try/To catch the wind.”

If it’s catchy fare you’re in search of, don’t buy this album. Jones has far more immediately gratifying LPs in her catalogue. I’m afraid I’ll never fall in love with her more overt jazz work, but that’s okay. This album is the loveliest trudge I’ve ever heard—an exercise in slowing things down to their breaking point. Which just highlights Jones’ voice, with which she does amazing things, unthinkable things, unbelievable things. I can imagine some people recoiling in horror at her interpretations of their faves. Too bad for them. She’s pleased to introduce herself, and she’s in no hurry to get acquainted.

GRADED ON A CURVE:

A