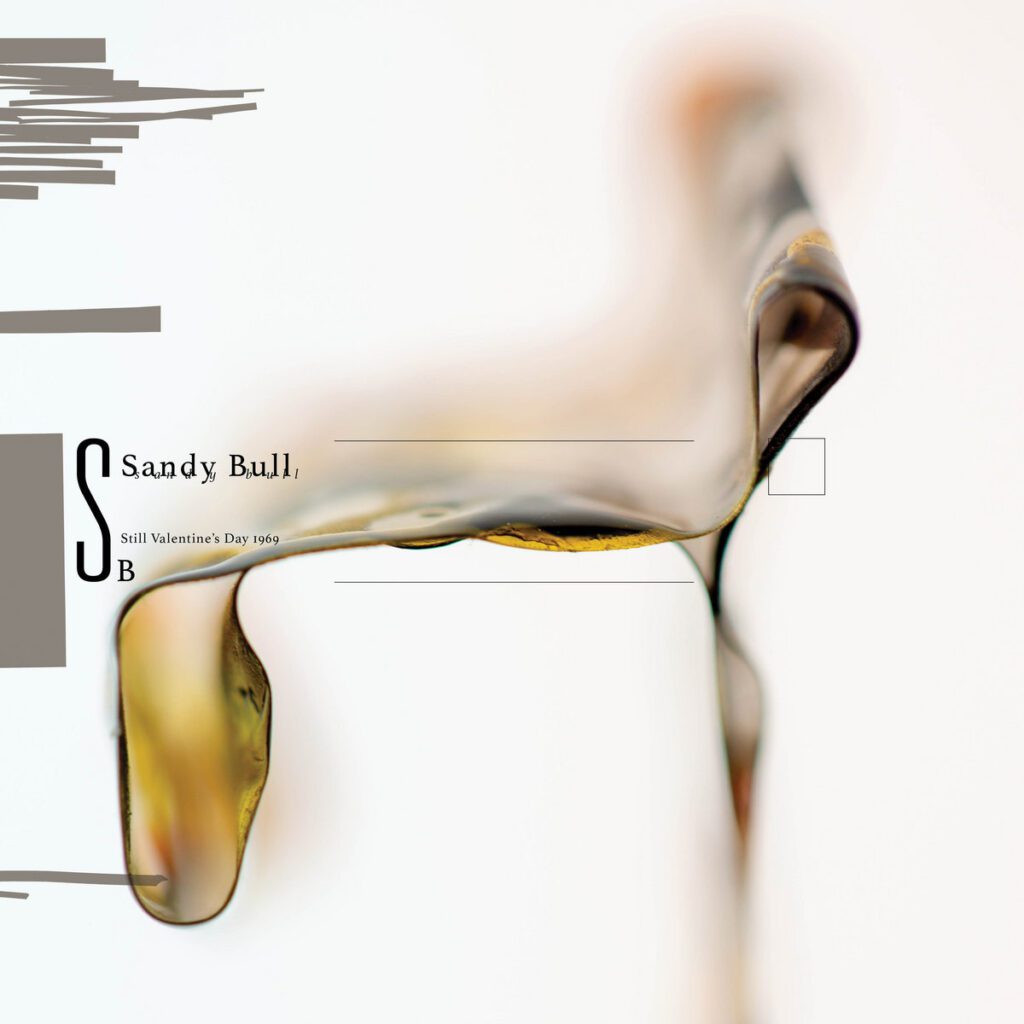

Extending from a rich folky bedrock and influenced by classical, Middle Easten music and even rock & roll, Sandy Bull was an undersung master of the guitar and other stringed instruments including banjo, bass, oud, and pedal steel. Having passed in 2001 with a modestly sized but often masterful discography, his reputation has been boosted by posthumously issued live recordings. The first one to surface, Still Valentine’s Day 1969, documenting two shows at the Matrix in San Francisco, was initially released CD-only in 2006 but has just received a terrific new edition on 2LP with the original liner notes by Byron Coley. Fans of Bull’s Vanguard years who’ve pined to drop needle on this set have reason to rejoice.

Long rated as a player of exploratory brilliance who was unfortunately burdened with addiction problems, Sandy Bull is accurately assessed as an early fusioneer whose stylistic innovations steadfastly avoided exoticism; between his 1963 debut Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo and its ’65 follow-up Inventions (both issued by Vanguard), Bull contributed percussion to ’64’s Music of Nubia (also released by Vanguard), the first album by Nubian music master Hamza el Din of Egypt.

Inventions offers Bull’s first recordings on the Arabic stringed instrument the oud, but his inclination toward a raga synthesis is already pretty clear in “Blend,” a 22-minute piece extending across Fantasias’ first side. However, Bull’s approach was multifaceted and way ahead of the pack for the era, as the great jazz drummer Billy Higgins is the sole accompanist on Fantasias and Inventions.

As underscored by his instrumental version of “Memphis, Tennessee” (closing Inventions and serving as the penultimate track on Still Valentine’s Day 1969) Bull was averse to merely swiping a few formal moves in service of broadening his sound. Instead, he favored a transformational approach to Chuck Berry’s rock & roll staple while retaining a sense of familiarity. This extends to 1969’s E Pluribus Unum, a wonderful shift into extended psychedelic environments with a deeper emphasis on electric guitar (a part of Bull’s arsenal from the beginning) that’s never simply taggable as rock.

Although Bull was experiencing some equipment issues on the nights that shape Still Valentine’s Day 1969, noting to the audience that his gear had been stolen and the Black Widow guitar he was playing was new to him, this reality lessens the impact of the two sets hardly at all. The album captures a flashpoint where Bull’s work with Higgins straddled the solo but extensively overdubbed E Pluribus Unum, the release of which was imminent.

Still Valentine’s Day 1969 opens with “Bouree,” a retitling of “Gavotte II, Pt. 2” sourced from Bach as heard on Inventions, and then rolls into a performance of “No Deposit, No Return Blues” that’s considerably shorter than the side-long studio take from Unum, but no less infused with reverb. To elaborate, Bull establishes some heavy tremolo (harkening back to his Pops Staples-influenced electric guitar on Fantasias’ “Gospel Tune”) as a sort of launching pad for self-generated interactions.

It’s a tactic that would grow into a bit of a signature, as Bull would continue to employ it on 1972’s Demolotion Derby (the least of his Vanguard LPs, but far from the disaster that some have described) and on Sandy Bull & The Rhythm Ace Live 1976, a record co-released in 2012 by Drag City and Steve Krakow’s Galactic Zoo Disk where Bull receives help from a primitive drum machine (the titular Rhythm Ace) in a slot opening for Leo Kottke.

The relative brevity of Valentine’s Day’s “No Deposit, No Return Blues” is perhaps reflective of cautiousness on Bull’s part; he was notably inconsistent in performance and the studio version of the piece hadn’t been released yet. Next is “Manhã de Carnaval,” the international sensation from that cornerstone of early art-house cinema Black Orpheus that was recorded for Inventions. Using a prerecorded backing track, Bull is more fully in a comfort zone that carries over into the first of the album’s two improvisations for oud and into the closing number of the first set, “Electric Blend.”

“Electric Blend” and “Electric Blend 2” clearly extend from the side-long side ones of his first two albums, but as both are soaked in reverb, and the latter, which serves as Still Valentine’s Day’s finale, especially acid-dipped, they more boldly reflect where Bull was headed with E Pluribus Unum. The use of a rediscovered practice tape with Higgins as a backing track for this album’s performance of “Memphis, Tennessee” is a swell deepening of this album’s already considerable allure.

Those new to Sandy Bull should begin with his first two albums and then dive right into Still Valentine’s Day 1969, proceeding after that into E Pluribus Unum and continuing forth as the music demands.

GRADED ON A CURVE:

A-