Celebrating Van Dyke Parks in advance of his 81st birthday tomorrow. —Ed.

Van Dyke Parks is easily one of the most eclectic and engaging musical minds of the last fifty years. Largely known for his involvement as lyricist in the resurrected phoenix that is The Beach Boys’ Smile, he’s also put his stamp on an array of important works, none better than his own 1972 masterpiece Discover America.

But to really crack the delicious and nourishing nut that is Mr. Parks, inspection of his solo work is an absolute must. Song Cycle, his 1967 debut is in obvious retrospect one of the truly amazing introductory statements in all of 20th Century music. I say obvious because hardly anybody bought the thing when it came out. This was due in part to his low profile. While he’d released a couple singles on MGM, he wasn’t exactly stormtrooping the era’s cultural radar.

But the main reason Song Cycle was destined for a second life as a cherished cult magnum opus lies in how Parks’ thoroughly non-trite baroque pop and gently psychedelic sensibilities synched-up with both his uncommonly deep and diverse interest in the history of popular song and the man’s shrewd ear for value in the contemporary (the record featured covers of both Newman’s “Vine Street” and Donovan’s “Colours”). With tenuous ties to the rock scene and a lack of capital with the rising tide of youth culture, it’s really no surprise Song Cycle took four years to recoup its admittedly large for the era $35,000 budget.

Ambivalent about his lack of success but undaunted, Parks bided his time by working with other artists through Warner Brothers. He did release a single in 1970, “The Eagle and Me”/”On the Rolling Sea When Jesus Speak to Me,” combining the A-side’s ‘40s-era Arlen/Harburg Broadway show tune with the flip’s radically interpreted cover of a gospel song by legendary Bahaman guitarist Joseph Spence. If the deck was stacked against Song Cycle in ’67, then by 1970 this single didn’t stand a snowball’s chance in a Hollywood hot tub. Needless to say, the record was scarce, apparently even at the time, to the point that many of Parks’ fans didn’t even know of its existence until Rykodisc utilized it as bonus tracks in their compact disc reissue program of his stuff.

If it appears that I dwell on this seeming one-off obscurity, it’s for a very good reason; the record sheds crucial light on what’s often been perceived as Discover America’s severe change in direction (and I’ll add that both tracks are now available on Arrangements Volume 1, a brilliantly enlightening collection of Parks’ early collaborations, and MGM stuff released on LP and digitally through his own Bananastan label). For if his second solo effort’s levels of stylistic departure still leave some people stumped, that once neglected single provides a key to understanding.

Discover America is a concept record, but not in the potentially frightening way familiar to rock bands with a surplus of aspiration. Simultaneously a tribute to classic Trinidadian calypso and a loose rumination on American history, it might initially (and for a while after that) seem to be totally out of step with the norms of 1972. But look closer and it becomes clear that it fell right into the decade’s breadbasket for nostalgic longing, a then somewhat new impulse that largely located the 1950s as The Good Old Days (think American Graffiti, Happy Days, Sha-Na-Na, chart hits by Chuck Berry and Rick Nelson, Grease).

Naturally, Discover America’s lasting importance is due in large part to its complexity and subtlety, factors that when combined with its seemingly casual, highly appealing music caused it to slip right by most critics at the time as merely an odd, inoffensive trifle. But make no mistake; Discover America is a rare and vital combination of sincere accessibility and bold, multifaceted ambition.

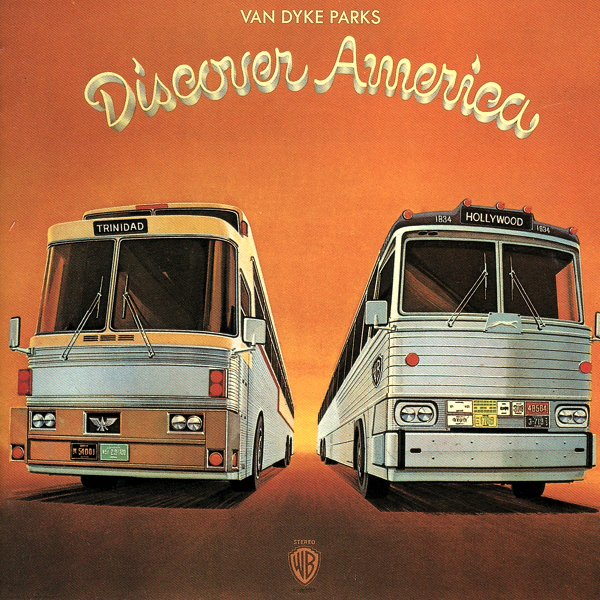

The proceedings start off rather strangely. A one minute clip of the great calypso singer Mighty Sparrow’s “Jack Palance” is immediately followed by “Introduction,” a twenty-five second bit of spliced tape recordings featuring an old man with a voice like heavy-duty sandpaper; meant to signify the talk of tour guides that frequented the busses of the album’s cover—to be frank the first time I heard it I was quite blindsided by its similarity to Captain Beefheart’s “The Dust Blows Forward and the Dust Blows Back.” And then to move directly into Parks smoothly crooning a cover of The Roaring Loin’s “Bing Crosby” provided a momentary study in sweet discombobulation.

Those worried over a lack of expertise regarding calypso need not be, for it’s as welcoming a musical form as there is. And it’s perfectly fine to ignore my advice; well done calypso reissues are numerous and widely available, with Rounder Records’ Roosevelt in Trinidad; Calypsos of Events, Places and Personalities being particularly illuminating as it includes originals of three of Discover America’s tunes, “Bing Crosby,” “The Four Mills Brothers” (also by The Roaring Lion) and “FDR in Trinidad” (by Attila the Hun). Parks shows the depth of his interest by including two from Lord Kitchener, three pieces of traditional origin and a fascinatingly strange tongue-in-cheek reworking of Sir Lancelot’s “G-Man Hoover,” a celebration of J. Edgar, late of the FBI.

But he didn’t limit himself to Trinidadian works. Two Allen Toussaint covers appear, “Riverboat” and a deliriously grooving cover of “Occapella,” very likely the album’s highpoint. And “John Jones” by ‘60s Trojan Records’ reggae singer Rudy Mills is given a lazily swinging treatment. But Lowell George’s “Sailin’ Shoes” is also present, and in markedly different form from the Little Feat original (released the same year!).

In fact Little Feat’s George and Roy Estrada both contribute to “FDR in Trinidad,” so fans of that band and George’s distinctive slide playing in particular should take note. But the most interesting instrumentalists included on Discover America are The Esso Trinidad Tripoli Steel Band, whose excellent Esso LP from 1971 was produced by Parks. Their mastery brings an authentic flavor that contrasts well with the record’s atmosphere of broad interpretation, specifically on the traditional “Steelband Music” and the quietly prescient statement on multiculturalism that is the LP’s coda, a short bit of Sousa’s “Stars and Stripes Forever.”

What slowly becomes obvious is that Parks genuinely loves Caribbean music; while respectful the record is never self-servingly so. And its concept holds a real point-of-view, examining the value in how other countries see and celebrate American culture. I’ve played the album many times specifically looking for a flaw, but by the start of the second side have always forgotten the task at hand.

Okay, at thirty-seven minutes and change, it still manages to feel too short. But the results of combined listening with Esso and Mighty Sparrow’s very fine 1974 Parks-produced Hot and Sweet LP are simply splendid. They extensively detail not only the huge scope of Parks’ interest and talent, but also show just how much amazing music is out there just waiting for discovery.

GRADED ON A CURVE:

A+