In the future, every tech company will have a celebrity advisor.

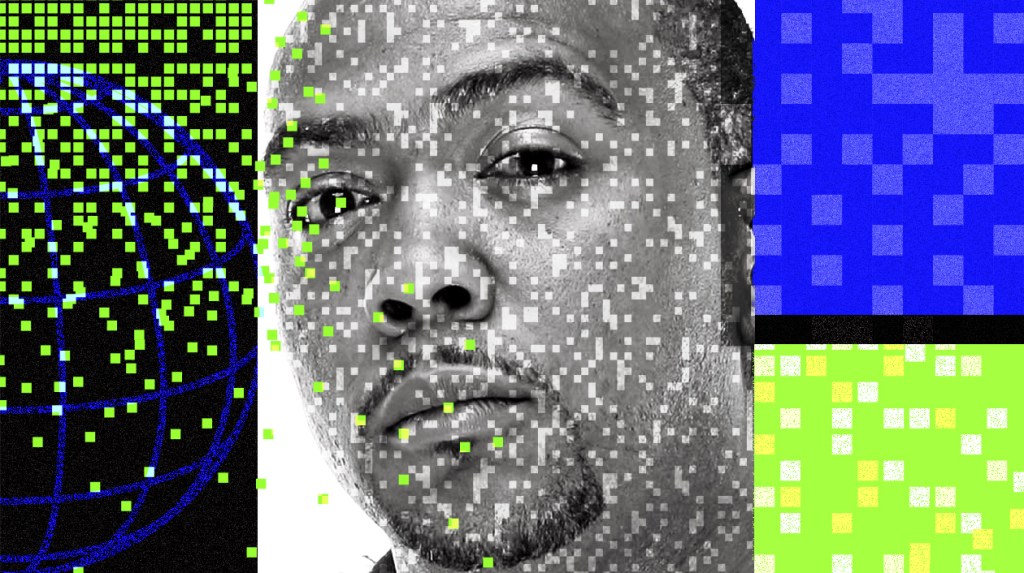

The latest is Timbaland, who is working with AI production company Suno on “day-to-day product development and strategic creative direction,” according to an announcement in late October. Timbaland is a hip-hop and R&B icon — a star songwriter, an innovative producer and a compelling performer. (His performance at June's Songwriters Hall of Fame gala was amazing.) As genius as Timbaland is, it seems reasonable to wonder where he finds the time to develop software.

It also seems reasonable to wonder if Suno hired him for more than just his vision. As Suno faces controversy and litigation from rights holders who argue that AI companies must license the music they use to train their software, Timbaland may be there to argue that it doesn't really matter. (Neither Suno nor a representative for Timbaland would comment on the nature of Timbaland's deal.) In other words, Timbaland is there to do for Suno what Limp Bizkit and Chuck D tried to do for Napster — Positioning the company with users but against the majority of creators and rights holders.

It seems like ancient history now, but within a month of Metallica suing Napster in April 2000, Limp Bizkit and Chuck D sided with the company against the band, Dr. Dre (who sued a few weeks later) and most of the music business. Limp Bizkit played a few weeks of free shows sponsored by Napster and the Bizkit frontman Fred Durst said the label offered fans a great way to sample albums before they bought them. Around the same time, Chuck D wrote a New York Times wrote in support of Napster and announced that he was partnering with the company in a contest. The company's subsequent bankruptcy filing contained reference to a payment to Chuck D for “speaking and endorsement costs,” according to Joseph Menit is excellent All the Rave: The Rise and Fall of Shawn Fanning's Napster.

Then, and perhaps now, the idea was to position a venture capitalist-backed startup on the side of artists. Suno is “the best tool of the future,” Timbaland said. “It allows you to get any idea out of your mind in your imagination.” Suno has already positioned itself as a disruptor, arguing in its response to the major labels' lawsuit that “What the major labels really don't want is competition.” Perhaps. But the lawsuit concerns Suno's alleged ingestion of copyrighted recordings in order to train its software.

This kind of maneuver is not that unusual. For decades, Silicon Valley has innovated with a predictable strategy: Ask for forgiveness instead of permission, then take political issues directly to users. That strategy, as well as the technology involved, has allowed Uber and Airbnb to grow so big that it can be hard to remember that they're basically high-tech ways to circumvent local taxi and hotel regulations. Uber and Airbnb essentially engage in regulatory arbitrage – they face less regulation than their legacy competitors, so they often come out ahead. And they managed to stay in business, at least in part, because they quickly got too big to fail. No politician wants to be known for making it harder to book a car or a hotel.

Suno and other AI production platforms are less problematic because they would compete more fairly with other music creation tools. The only question is whether the company will have to compensate the rights holders — including, possibly, Timbaland himself. The lawsuit against Suno is going to get complicated — one of these AI cases could end up in the Supreme Court. But creators who want to be compensated for the use of their work aren't against AI music tools any more than Metallica is against digital distribution — they want to be paid for the use of their work.

At least one creator will almost certainly make a lot of money from Suno: Timbaland. And while it may seem bad for him to be on the other side of the issue than most musicians, this was a reliable way to make money. One of the big winners of the Early Digital Music Age – the introduction of Napster in 1999 to Spotify's US launch in 2011 – was Alanis Morissette.

Yes, really.

When MP3.com sponsored one of her tours in 1999, Morissette invested $217,355 in early-stage stock in the company, which — well, it was never entirely clear how it would actually make money, but that address was very hot at that time. He made more than a million dollars by selling only part of the stock.

At the same time, it is worth remembering how these movements look years later. From the perspective of 2024, it seems smart that Metallica and Dr. Dre sued Napster because the company's demise paved the way for licensed, commercial streaming services. Cracker frontman David Lowery and Taylor Swift can also say they were on the right side of history when it came to copyright. In retrospect, Limp Bizkit and Chuck D seem a little naive. Years from now, Timbaland, as talented as he is, may look the same.

from our partners at https://www.billboard.com/pro/timbaland-standing-suno-what-does-mean-creators/