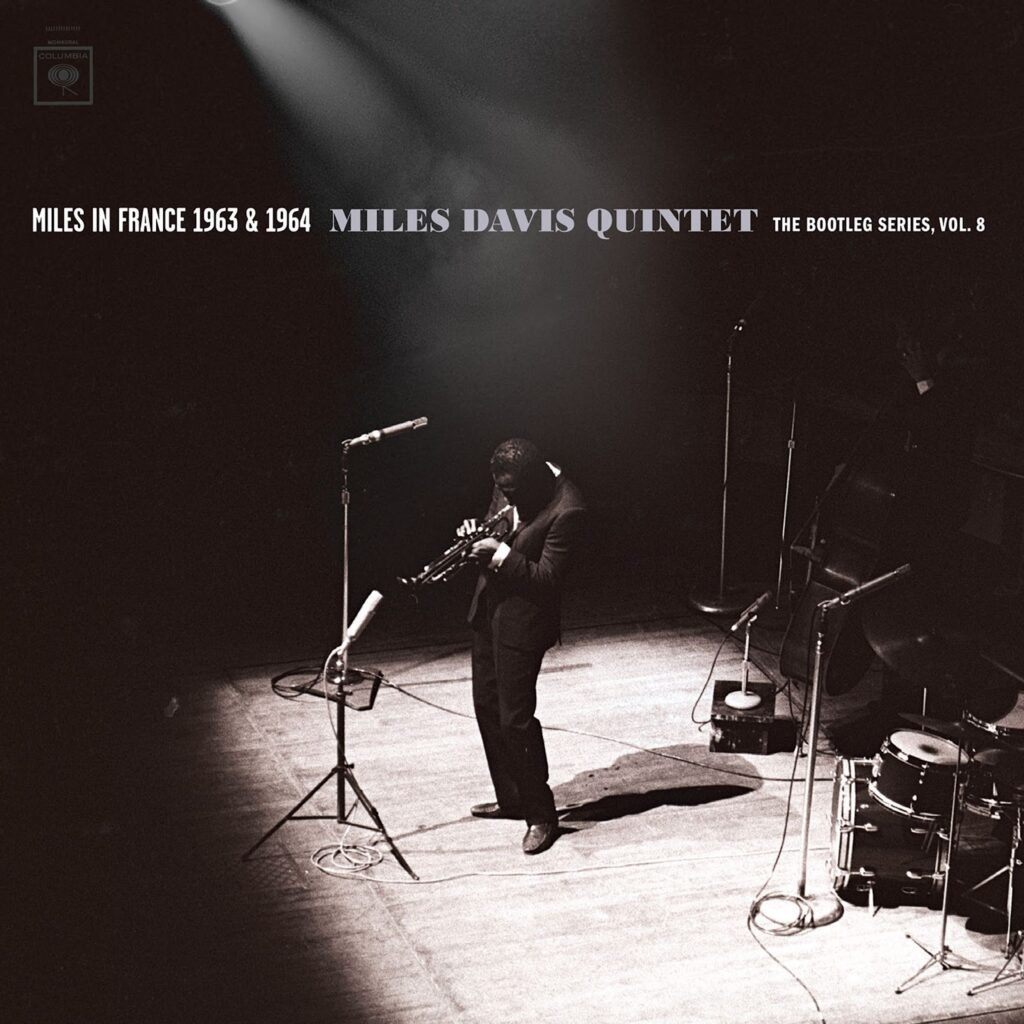

VIA PRESS RELEASE | The acclaimed Miles Davis “Bootleg Series” has spanned years as early as 1955, and as late as 1985, but it has not yet touched 1963 or 1964—a pivotal period in Miles’ musical evolution and the auspicious beginnings of the Second Great Quintet—until now.

Miles In France will arrive November 8th as a 6 CD and 8 LP set with more than four hours of previously unreleased music and new liner notes by journalist Marcus J. Moore. A 2LP break-out set, of just the 1964 recordings, will also be available. The release will also be available digitally in its entirety on DSPs. Pre-orders begin today HERE.

Miles in France – Miles Davis Quintet 1963/64: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8 was produced by the multi-GRAMMY winning team of Steve Berkowitz, Richard Seidel, and Michael Cuscuna (marking one of the last productions for Cuscuna, who passed away earlier this year) and mastered by multi-GRAMMY winning Sony Music engineer Vic Anesini at Battery Studios in NYC.

France was important to Miles on both a professional and personal level, quickly becoming his preferred live market. He played in France more times than any other country outside the U.S. and recorded there frequently. His history in the country goes back as far as 1949—when he appeared at the Festival International De Jazz at just 22 years old—and as late as July 1991, for a concert in Nice just two months before he passed.

In the early 1960s, Miles came to France having altered the course of jazz. His 1959 landmark album Kind of Blue eschewed hard bop for a modal style that allowed room for a freer type of improvisation—an overcast slow-burner evoking ease and tension. But when compared with the studio version of Kind of Blue, the music coming out of the Quintet in Antibes and Paris had very little room for space and silence. The highs were dramatic and the lows were filled with powerful phrasing—adding fresh perspective to this landmark album in all of jazz.

Miles officially hired the rhythm section of Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, and Tony Williams on drums in the Spring of 1963, and they went into the studio in May of that year with George Coleman on tenor saxophone to record the second half of the Seven Steps To Heaven album. Two months later they arrived in Europe, and Downbeat deemed their performances at the 1963 Festival Mondial Du Jazz to be: “superb… [Davis] was in clean, decisive form and at his lyrical best…”

Ron Carter recalls the experience in the new liner notes, adding, “I had never played with anyone like that, of course, and certainly not for this extended period of time. It was just stunning to hear him play like this, play with that intensity, play with that tempo, play with that direction night in and night out and not turn it on to the band and say, ‘Stop that.’ He allowed us to do whatever the chemist allowed his proteges in the lab to do. Take these chemicals I’m giving you guys and see what we come up with. Just call the fire department if necessary.”

Miles would return to the U.S. with a new sense of musical purpose, spurred on by the bands he took to France, reveling in the stages they played. By the time Miles recorded E.S.P. with the Second Great Quintet in 1965, he proved that—despite whatever physical and spiritual challenges he may have endured—he was the barometer by which jazz moved and evolved. Some 60 years removed from these recordings, and more than 30 since his passing, Miles is still the summit and pinnacle, the essence of audacity, the monument of all monuments.