The Stray Cats were the Sha Na Na of the MTV era. A rockabilly nostalgia act, and like most nostalgia acts they offered up a tame version of the music produced by the folks they were paying tribute to—Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, Wanda Jackson, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis Presley, Johnny Burnette—and the list goes on. They carried the torch. But they forget to light the damn thing.

The Stray Cats hued to the original sound, but they were far too polite—the early rockabilly crowd was composed of berserkers, and the Stray Cats were more Apollonian than Dionysian. The early folks were out to burn the cornfield. The Stray Cats were out to pay their respects. They had sound and image down pat but they weren’t into arson.

They left that to rockabilly’s other modern day practitioners—bands like the Cramps, the Reverend Horton Heat, the Hillbilly Hellcats, Flat Duo Jets and Southern Culture on the Skids, to name just a few. Bands that injected their rockabilly with a healthy dose of run-amok dementia. Guitarist and vocalist Brian Setzer had the right haircut and he sure could play, and the same went for drummer Slim Jim Phantom and bassist Lee Rocker. But what I never heard from them was the barbaric yawp that made their models menaces to the social mores of their day. They weren’t dangerous—tribute bands never are.

I’m certainly not the first person to question the Stray Cats’ overly respectful and ultimately weak-kneed take on one of rock’s most primal genres. Rolling Stone’s David Fricke bandied about the word “spiritless,” while Robert Christgau went for the jugular, writing that Seltzer’s “mild vocals just ain’t rockabilly. You know how it is when white boys strive for authenticity—’57 V-8 my ass.” Later he would get even surlier, writing, “Brian Setzer is the snazziest guitarist to mine the style since James Burton. But he’s also a preening panderer, mythologizing his rockin’ ’50s with all the ignorant cynicism of a punk poser. He’s no singer, no actor, no master of persona. And if he can write songs he didn’t bother.” Ouch.

The Stray Cats are beloved by many, and good for them. But they did so by defanging rockabilly—they took it and went Happy Days on its ass. They smiled while Jerry Lee Lewis was setting his piano on fire, shooting his own bandmates and getting arrested for possession of enough pills to stone entire states. And most listeners had nothing to compare them to. They’d never listened—and I include myself here—to the likes of Gene Vincent and Wanda Jackson. Their derangement quotient was nil. They weren’t going to scare your parents or turn you into a juvenile delinquent enemies of the state. They were safe as the aforementioned milk.

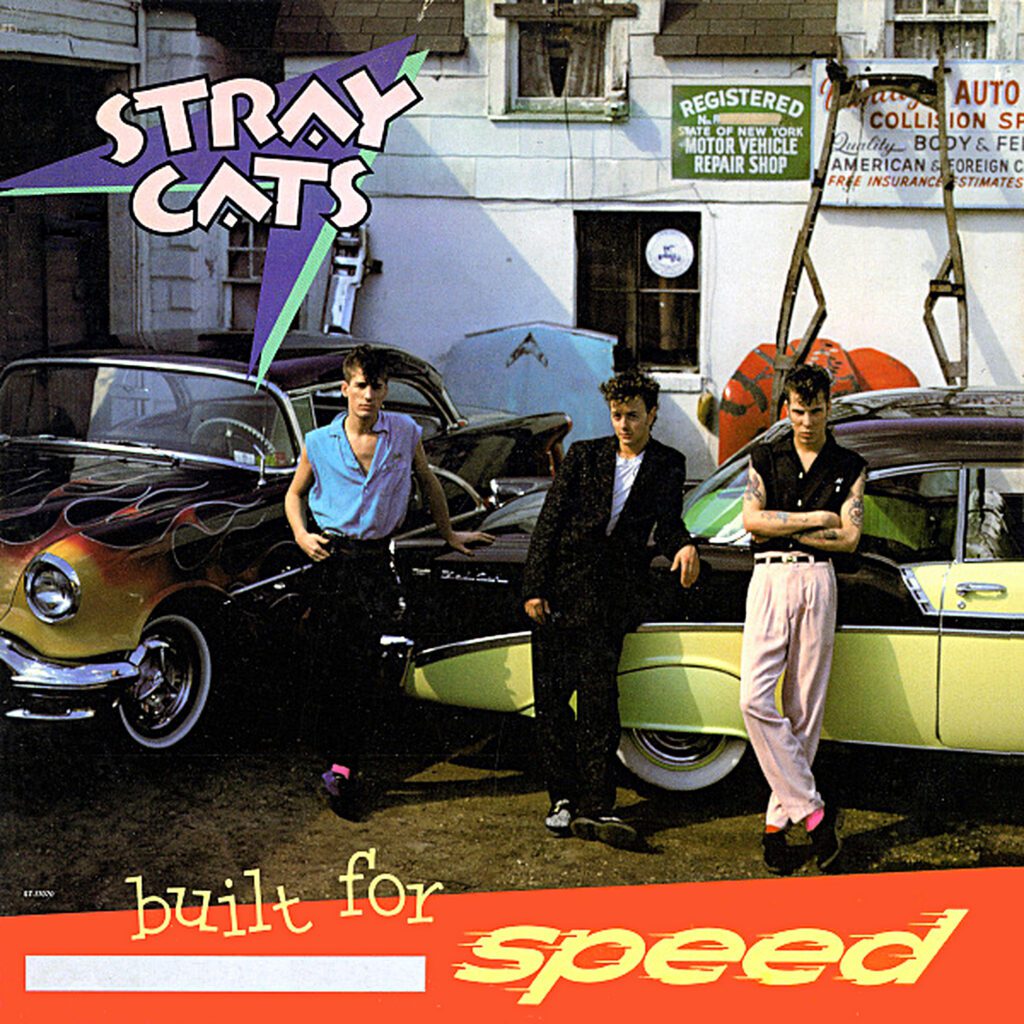

The Strays Cats (who were Long Island boys) first broke big, expat style, in England, and their first two LPs (the successful Stray Cats and the letdown Gonna Ball, both from 1981) weren’t even released in the United States. American listeners had to wait until 1982, when EMI America Records released Built for Speed, a compilation that culled eleven tracks from the English releases along with the title track, which had never been released in the UK. Built for Speed promptly rose to the No. 2 spot in the Billboard 200 and ultimately went platinum. Talk about your cat scratch fever.

The problem, for me anyway, is that the songs on Built for Speed sound like the product of spay cats, not stray ones. There’s nothing feral about them—on the contrary, they sound downright domesticated. Setzer wrote some finger-popping catchy pop songs—I disagree with Christgau on that score—and the band is tight, but the Stray Cats didn’t didn’t have an unhinged bone in their collective feline skeleture.

Take “Rock This Town”—great intro, jaunty and infectious melody and a real humdinger of a sing-along. And Setzer’s guitar solo steams. But as much as Setzer tries to put some heat in his vocals, he can’t quite pull it off. And in the end what you have is a song that I can say without doubt would sound better with Linda Ronstadt—who had more wildcat in her than all three Stray Cats combined—doing the honors. As for “Stray Cat Blues” it’s a wet match of a walking bass bore. It doesn’t jump and shout, it doesn’t scream—the boys play it slinky and the boys play it cool, daddy-o, but it sounds like a dull walk through the graveyard of the rockin’ fifties and hand-me-down American Graffiti to me.

“Built for Speed” could use more horsepower—doesn’t sound like Setzer’s cruising in a machine with a “V-eight engine with the fuel injection” to me—but it has a slightly rawer feel than much of their music. Setzer summons up a bit of that old rockabilly spirit, although you’re not going to mistake him for Gene Vincent, and he lets his guitar do some of the loudest talking. And while we’re on the subject of classic automobiles, “Rev It Up and Go” does just that, Chuck Berry style. Unfortunately Setzer doesn’t sound like a wild man on this one—frankly, he sounds like a wuss. Plays one sizzling hot guitar solo, though. And I like the group vocals at the end.

“Little Miss Prissy” is as raunchy and undomesticated as the Stray Cats get—it’s a garage rock number that borrows liberally from the Rolling Stones’ “It’s All Over Now,” which the Stones swiped from Bobby and Shirley Womack. It boasts a ferine guitar riff and the guys sound like they’re having fun banging it out, and Setzer again rises above his station, both vocally and on the six-string razor. Nice stuff.

“Rumble in Brighton” has rumble power, sounds like TV show theme music to me, but okay. The song’s biggest problem is Setzer doesn’t sound like a rumbler—he comes off as a nice guy trying desperately to convince you he’s up for a street fight. Even that “goddamn” sounds wimpy. “Runaway Boys” ain’t much—the big bad bass and drum slap intro are promising, but the melody is a non-starter and Setzer’s vocals are wooden nickel cheap. And when push comes to shove about all you’re getting for your wooden nickel is some nifty reverb on the guitar.

“Lonely Summer Nights” is nifty Grease soundtrack crooner fare, complete with a dreamy saxophone solo. Is Setzer up to handling the vocal requirements? Barely. Fact is I’d sooner hear John Travolta sing the damn thing. But it’s a welcome change of pace from the rockabilly, and it breaks my greaser heart to watch the old phonograph needle slip into the next groove, the upbeat Elvis-like shuffle that is “Double Talkin’ Baby.” Setzer doesn’t convince (even when he’s screaming!) but does, to his credit, play rockin’ guitar all over the damn thing. I’ll never be as impressed by his playing as much as I am by X’s Billy Zoom, but it’s an incontrovertible fact that he never wastes a note and has added to the rockabilly guitar vocabulary.

“You Don’t Believe Me” is a bluesy slide-guitar number and kinda makes me think of Rockpile, that’s how slick the production (and Setzer’s vocals are). I’m not a fan for the simple reason that it’s a pop song but a not very irresistible pop song. And the good people of the United Kingdom agreed—the only single released from Gonna Ball, it gasped its way to the #57 spot on their pop charts before coughing twice and dying.

The album’s pair of closing tracks are both covers. “Jeanie, Jeanie, Jeanie” was an Eddie Cochran number originally released in 1958, and to their credit the Stray Cats’ version has a rawer, raunchier sound than most of their fare—why, it might have come straight out of Sam Phillips’ Sun Studio. There’s no slick pompadour pomade in Setzer’s vocals, and the playing’s downright riotous. It’s my album fave.

Wish I could say the same about album ender “Baby Blue Eyes,” which was first recorded by Johnny Burnette and the Rock ’n’ Roll Trio. Burnette was a big influence on the Cramps, which tells you something about his approach to the genre. Needless to say the Stray Cats version is slicker, more civilized—house-trained. But Setzer does his best, although I’d be remiss not to say I’ve rarely heard a less convincing screamer—how you make a scream sound polite is beyond me.

Let’s face it—Jerry Lee Lewis would have eaten the Stray Cats for breakfast, bones and all. Wanda Jackson may have spit out the bones, but I doubt it. But that wasn’t what the Cats were about—they were making, for better or worse, sanitized rockabilly for the masses. And at that they succeeded, and if that’s what you’re after they did a damn fine job of it. But I’m hardly the only person who thinks they’re watered-down whisky, and the only place they could have rocked apart was the main street five & dime. They were selling a pale simulacrum of the real thing to folks who’d never heard the real thing, but they filled a void.

Me, I’d much sooner listen to the original practitioners, or their psychobilly contemporaries. “Nostalgia,” wrote the late newspaper columnist Doug Larson, “is a file that removes the rough edges from the good old days.” File the Stray Cats under “File.”

GRADED ON A CURVE:

C-